Are US markets sleepwalking into an inflationary shock?

NBR Articles, published 15 July 2025

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall,

originally appeared in the NBR on 15 July 2025.

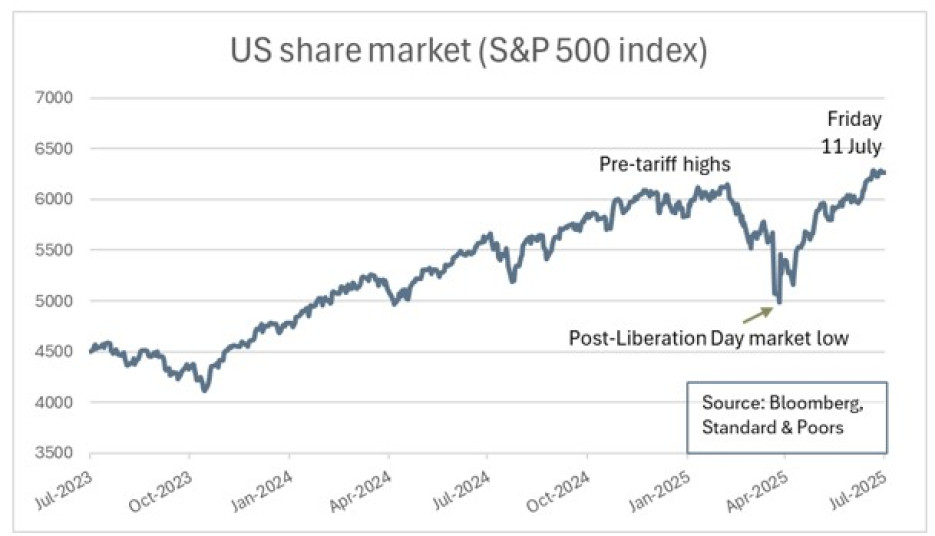

Since the initial sharp reaction to Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariff announcements, US markets have fully recovered. Consider the following:

The US share market is trading 2% higher than its February highs, and it is more than 25% above the lows it reached in early April, in the aftermath of liberation day:

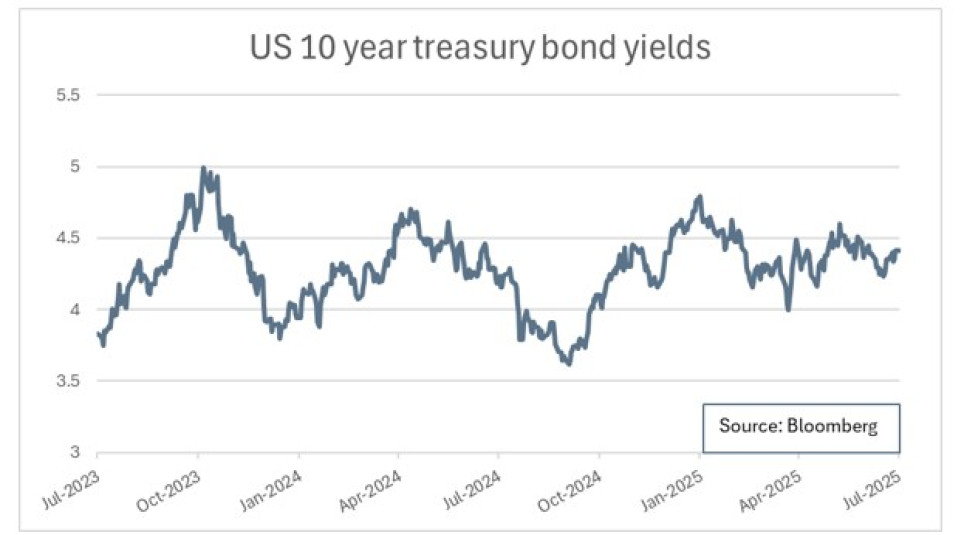

US 10-year treasury bonds are yielding 4.41%, only slightly above the average yield of 4.28% that has prevailed over the past 2 years:

The inflation rate priced into the US 3-year inflation swap market has only risen slightly, to 2.77%, just 0.22% higher than the average inflation rate priced into this market over the past 2 years:

These market indicators would seem to indicate that market participants are no longer concerned about the impact of higher tariffs on US inflation.

Why even try to take a view on the US inflation outlook?

Normally, I don’t invest many brain cells trying to second-guess markets on the US macroeconomic outlook. If you want to add value to an investment portfolio, it’s best to identify a few areas where you can realistically expect to build more insight than the majority of other market participants, and to concentrate on these areas, whilst avoiding staking much on issues where it may be difficult to gain superior insight over other market participants.

Most of the time, taking views on the outlook for the US economy seems to fit clearly into the “too difficult” category. Too many smart people are thinking about the outlook for the US economy for it to be a profitable use of my time to try to out-think them, so I normally don’t.

However, markets don’t always get macro right. The apparent willingness of the financial markets of today to shrug off concerns about how huge changes in tariffs could impact inflation and/or corporate profitability feels eerily similar to the period leading up to the global financial crisis (late-2006 to mid-2007), when quite a few commentators were making a lot of noise about increasing credit defaults in sub-prime loans, but US equity market participants plugged their ears and kept on buying equities for several months before the issue became so large that they could no longer ignore it.

What could be the impact of higher US tariffs?

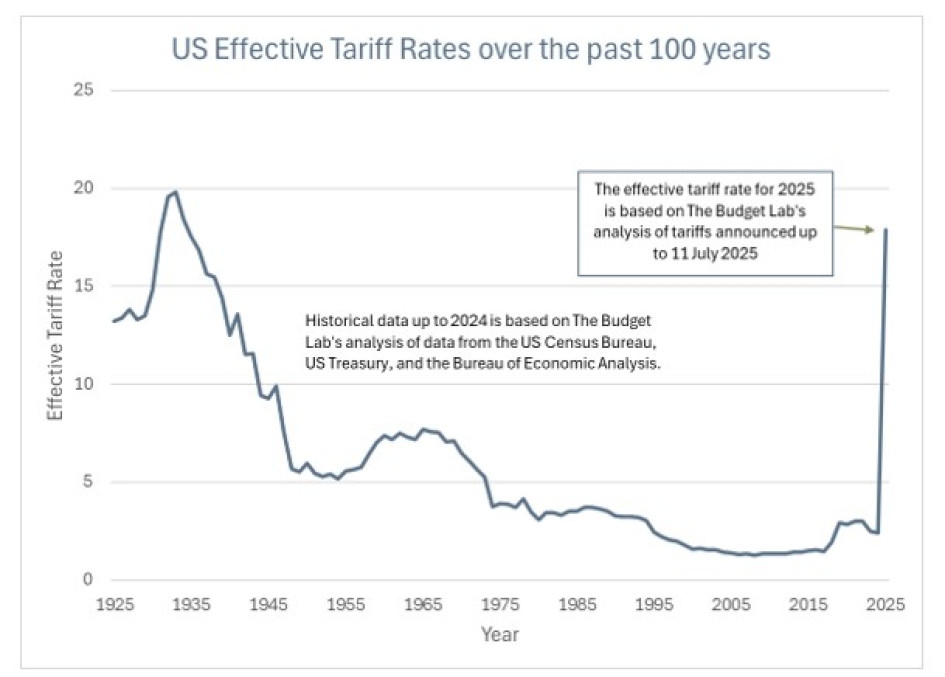

Since “Liberation Day”, Trump has announced a number of changes in tariffs applied to different countries and/or commodities. The Budget Lab of Yale University has calculated that based on the tariffs announced up to 11 July (but excluding the “reciprocal tariffs” that Trump is currently advising countries that their exports will face from 1 August), America’s effective tariff rate will increase to 18.7%, but this will likely drop to 17.9% as importers substitute between source countries in response to these tariffs (JP Morgan recently calculated a slightly lower effective tariff rate of 14.9%, but this seems to be prior to various recent tariffs such as the 50% tariff on copper imports and the recent increase in tariffs on Canada).

As the graph below shows, the announced tariffs represent a huge increase compared to the 2024 effective tariff rate of 2.4%.

As alluded to above, this graph only tells half the story, as it excludes the “reciprocal tariffs” that are currently being planned for the 1 August, and also excludes mooted tariffs, such as Trump’s stated intention to place tariffs of up to 200% on pharmaceutical imports if pharmaceutical companies do not shift their production to the US or the threatened further 10% tariff on BRIC countries if they implement any “anti-American” initiatives.

In simple terms, the tariff increases formally announced (as of last week) will increase the cost of goods imported into the United States by an average of about 15%. How could this not be inflationary? The US economy is admittedly quite insular, with imports of goods only amounting to 11.5% of GDP. However, a lot of US-produced goods will also be priced to import parity, particularly in commodity or near-commodity markets.

A simple analysis would suggest that businesses will be paying extra costs amounting to over 1.7% of GDP, so either prices should go up by 1.7% or corporate margins will be squeezed. This is pretty close to The Budget Lab’s estimate of a +1.9% initial impact on inflation, reducing to +1.6% over time as companies use substitution in their supply chains.

The economic context in which these tariffs are being raised also seems to increase the probability that the tariff hikes will feed through into inflation. Notably, the US economy currently has high budget deficits, a declining currency, low unemployment, reduced migrant worker availability, and is flush with liquidity / money supply. All these factors tend to be inflationary in and of themselves, which suggests quite a risk of some ugly inflation outcomes when these factors combine with the inflationary impacts of higher tariffs.

While the inflationary impact of higher tariffs might not be a big deal if it proved to be purely one-off, there is a significant risk that wages and salaries adjust to at least partly compensate workers for the increased cost of living. If these higher wage costs in turn get passed through to selling prices, tariff increases could kick off a vicious wage-inflation cycle that could take some years to tame.

Monetary Policy

US interest rate markets are currently pricing in an expectation that US monetary policy is more likely to be eased than tightened over the coming year.

It may seem strange that markets expect an easing in monetary policy when tariffs are about to add 1.8% to inflation. The key factor causing fixed interest markets to price in easier monetary policy will be that core inflation has dropped from 6.6% in late 2022 (caused by a spike in commodity prices) to 2.8% in the year to May 2025, but the Federal Reserve’s target for the overnight interest rate has so far only been reduced by 0.75% (from 5.25% to 4.50%). Monetary policy tends to move like a super-tanker – moving steadily in one direction for a long time and taking an equally long time to change course – so current market pricing is effectively assuming that current momentum will keep pushing the monetary policy super-tanker in the direction of lower interest rates.

If tariffs add something like 1.8% to the inflation rate over the next few months, interest rate markets could easily be disappointed in their expectations for a continued easing of monetary policy. This would be a shock to bond markets, which would likely also flow through to equity markets.

US bond yields averaged 2.2% between 2010 and 2021 but now sit at 4.4%. Meanwhile, the earnings yield on the US equity market has declined from an average of about 5% over the 2010 to 2021 period to less than 4% today, suggesting that the US equity market has not yet even adjusted to the reality of higher current bond yields. Accordingly, there seems to be little room for the US equity market to sustainably absorb any further increase in US bond yields.

Recession?

Higher tariffs could have various adverse impacts on US economic demand:

- Consumers may react to higher prices by cutting spending, particularly for durable items, where “sticker shock” will often cause people to put off making purchases. Durable items will generally be more affected by higher tariffs than everyday items such as groceries, as they are more frequently manufactured outside of the United States.

- Some businesses may have to lay off staff and reduce production if they struggle to pass on the higher costs they face through imported materials, components, and other inputs.

- Other businesses may reduce plans for capital expenditure if high tariffs on imported machinery, components, and commodities (such as copper and steel) push up the cost of building new plant.

- Specifically, the data centre building boom could decelerate or move offshore as big tech companies contemplate higher build costs (due to increases in the cost of imported electronic components) and as tariffs on energy imports from Canada push up the cost of US electricity.

The US economy will likely also be hurt by counter-measures that countries in the rest of the world take in response to US tariffs. These could include counter-tariffs imposed on US-made goods, but we must also consider non-tariff responses, such as Canada re-orientating its defence spending from US-made armaments towards European-made armaments, and Canada’s plans to shift spending on data and software from US big tech companies towards Canadian-developed alternatives. Europe is holding off from announcing what counter-measures it will take until after 1 August, but if it fails to reach agreement with the US, measures that will impact US big tech companies seem almost inevitable.

Obviously, the negative effects of higher tariffs on some businesses will be at least partially offset by other businesses benefitting from the protection of higher tariffs. Although most economists are anticipating a negative impact on US GDP from higher US tariffs, most reckon the impact to be less than 1% of GDP, so not big enough in itself to lead to recession.

The upcoming June quarter results season may help provide some clarity on the impact of higher tariffs, as we will hear US companies talking about how the current environment is affecting demand, profitability, and their capital expenditure plans.

Winners and Losers

Higher tariffs will help most companies that are manufacturing and selling in the United States (particularly if they’re competing with imports), but will hurt most companies that are manufacturing outside of the United States, retailing imported goods in the US, or operating US-based services businesses that rely on a lot of imported goods.

Unfortunately, when you read down the list of America’s most highly-valued listed companies, you find a lot more losers than winners.

Many highly-capitalised US companies that sell physical goods are primarily having these goods manufactured outside of the United States (e.g. Nvidia, Apple, Broadcom, Eli Lilly). Although there are some large companies that are potentially winners from tariff protection (e.g. Tesla, Proctor & Gamble, General Electric), they don’t add up to a large share of the capitalisation of the US share market. Large retailers like Amazon, Walmart, and Costco will likely be hurt, as they import a large share of their non-grocery items from China and other developing economies.

As a general observation, it seems that the larger a company is, the more likely it is to source its products internationally. When you’re investing in the US share market, you’re typically buying large companies selling goods or services around the world using international supply chains, not the local furniture maker or fashion designer who may be struggling to compete with cheaper imports. Even if the total value of “tariff wins” was equal to the total value of “tariff losses”, you would not see this from investing in the S&P 500 index.

Conclusion

After an initial panicky response to the liberation day tariffs, US financial markets (and the US share market in particular) have recovered to a level which seems to imply that tariffs will have minimal impact on inflation, interest rates, and corporate profits. This seems to be an excessively sanguine response to some dramatic changes to US economic policy, which have the potential to set off an inflationary cycle and severely hurt some businesses. Accordingly, it is quite probably a bad time to increase your allocation to the US share market.

Nicholas Bagnall is Chief Investment Officer of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited, and an investor in the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios (including the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund) that invest in global equity markets, including the US equity market. These portfolios hold the following companies mentioned in this column: Nvidia, Apple, Broadcom, Proctor & Gamble, Amazon, and Walmart.