Bitcoin, The Ultimate Unethical Investment

NBR Articles, published 3 February 2021

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall, originally appeared in the NBR on 3 February 2021.

Over the past 4 months, the market price of bitcoin has more than tripled, from US$10,700 per bitcoin in September 2020 to US$34,000 today. At today’s prices, the market value of all bitcoins in existence is about US$630 billion, and the combined value of all crypto-currencies is close to US$1 trillion. Five years ago, bitcoins were trading at US$370, so today’s price represents a 92-fold increase over 5 years.

Anecdotally, the rise in the bitcoin price has drawn in more and more retail “investors” who seemingly buy bitcoin in the hope that it may show similar price appreciation over the next few months to what they can see it has done in the recent past.

For bitcoin buyers who feel the need to affirm that their investment has some solid fundamental grounding, there seem to be two key lines of argument:

- Bitcoin might supersede or join gold as a safe store of value, and future central banks and individuals will likely hoard it in the expectation that it will provide reasonably certain realisable value in future crises; and/or

- Bitcoin will replace central-bank issued currencies as an accepted medium of exchange.

Bitcoin as a store of value?

The key argument for bitcoin becoming accepted as a safe store of value is that there is a limited supply of bitcoins – the algorithms that govern bitcoin ensure that there will never be more than 21 million bitcoins in existence (only 13% more than the 18.6 million bitcoins that are already circulating amongst terrorists, drug dealers, and hipster investors). Bitcoin is therefore protected against supply-induced inflation, and will not become worthless for the same reasons that the currencies of places like Zimbabwe and Argentina have in the past when their governments printed too many notes.

But bitcoin lacks many of the other characteristics of stability that have allowed gold to maintain its status as a perceived safe store of value. For example:

- It is not stable. Bitcoin has an annualised volatility of about 96%, compared with 16% for gold. (I measure this using 4 years of monthly returns, measured in NZ dollar terms).

- There are no intrinsic uses for Bitcoin that can give us any comfort that its value will increase with inflation. By contrast, gold is used for jewellery and electronics, and this demand has a stabilising effect by tending to increase when the price of gold declines.

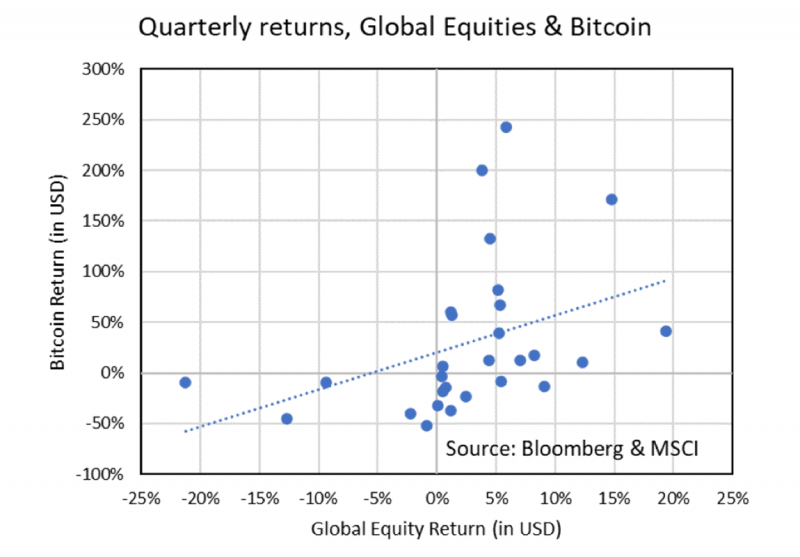

- The price of bitcoin seems to be highly sensitive to equity markets, and therefore fails to function as a diversifier within an investment portfolio. Based on the pattern of monthly returns over the past four years, bitcoin has a beta of 2.56, meaning that it tends to amplify any movement in equity markets two-and-a-half-fold. In the event of equity markets declining 20%, our best guess should be that bitcoin would fall 50%. The graph below shows quarterly returns from Bitcoin and from Global Equities over the past 5 years. As can be seen from this graph, bitcoin has declined in every quarter that global equity returns were negative. By contrast, gold shows very little correlation with equity markets, showing a beta of just 0.02 over the past 4 years.

- There is a long history of people placing high value on gold, but only a short history of people placing a high value on bitcoin. Logically, if you are a looking at any phenomenon that will ultimately have a measurable duration, there is (in the absence of any other information) an equal probability that you are observing it in the first half of its life as there is that you are observing it in the second half of its ultimate life. Hence, if we observe that humans have been placing significant value on gold for 8,000 years, we may infer that there is a 50% chance that they will continue to place significant value on gold 8,000 years in the future. But for Bitcoin, the same logic would imply that there is a 50% probability that bitcoin may have little value within 8 years’ time. While there may be some prospect that bitcoin is the “next gold”, there seems to be a higher probability that it is just another example of the investment bubbles that have periodically generated speculative enthusiasm since at least the Dutch Tulipmania of the 1630s. The fact that people have been chasing bitcoin for about 8 years now suggests that balance of probabilities is that demand for bitcoin will outlive the current enthusiasm for GameStop shares, but it has not yet persisted for sufficient time to be confident that demand for bitcoin will persist for centuries into the future.

- While it is still possible to lock gold in a vault, we do not know how long bitcoin will be secure. Bitcoin security relies on public key encryption, where a hashed version of everyone’s password is stored on thousands of computers around the world, but no one can currently use this information to work out people’s passwords, because the encryption uses algorithms that can be easily calculated in one direction but are extremely difficult to solve in reverse. For example, many 10 year olds using no more than pen and paper would take only a couple of minutes to calculate that 431 times 1,237 equals 533,147, but conversely the smartest mathematician (without access to computing power) might take hours to work out the two prime factors of 533,147. The public key encryption used by bitcoin essentially just uses a much more difficult version of this problem. There seems to be a genuine risk that within the next decade quantum computing could advance to a point that makes it far easier to solve these sorts of problems in reverse. When quantum computing reaches this point, someone will inevitably conclude that taking money out of bitcoin wallets is the most lucrative use of the new technology!

Bitcoin’s current capitalisation of US$630 billion compares to an estimated value of US$12 trillion for all the gold that has ever been mined, suggesting a best case 20-fold increase if bitcoin were to totally supersede gold. However, a lot of the gold that has been mined in the past is currently being used in jewellery or electronics, or has ended up back in the ground in cemeteries and landfills, so the amount of gold that’s being held as an investment may be less than half of the quantity that was originally mined.

Bitcoin as a medium of exchange?

But what about bitcoin’s value as a medium of exchange? Bitcoin fails on this measure as well. Although some businesses are starting to accept bitcoin as payment, they invariably prefer to set prices in terms of a relatively stable currency which doesn’t force them to change prices every day. Further, bitcoin’s distributed ledger makes it an inefficient form of payment, gobbling up several thousand times as much electricity (and hence, carbon emissions) per transaction than electronic transactions conducted using Visa or Mastercard.

The architecture of bitcoin also limits its global use to no more than about 7 transactions per second. By contrast, in New Zealand alone, we apparently hit 204 eftpos transactions per second at 12:30pm on Christmas Eve. On the face of it, Bitcoin has only just enough global capacity to handle the peak electronic transaction demands of a city like Tauranga.

Under its current architecture, Bitcoin is not going to supersede conventional currencies as a medium of exchange. It seems to have a lot of appeal to drug dealers, terrorist financers, child pornographers, money launderers, and even mere tax avoiders who want to conduct transactions in a way that cannot be traced by the authorities, but for people who earn and spend their money in a legitimate manner, the advantages of paying through bitcoin are hard to identify.

Bitcoin as a tool for speculation?

There is a peculiar paradox to particularly volatile speculative markets, which is that the mere fact of their volatility creates a positive skewness to the distribution of potential returns that can make the expected value of short term returns seem attractive, even to those who acknowledge that the longer term outlook is a probable bust.

As a simplifying example, I might hypothesise that each year bitcoin has a 60% chance of declining by half and a 40% chance of doubling. Roll those probabilities ahead by enough years, and it is inevitable that the years in which it halves will end up out numbering the years in which it doubles, such that its value will most likely decline over time. But for any individual year, the mathematical expectation for returns (under this example) would be positive, as the 40% chance of a +100% return outweighs the 60% chance of a -50% return, such that the expected return for each year could be calculated as +10%. Taken to its extreme, someone who believes in these probabilities might rationally invest a portion of their investment portfolios in bitcoin each year until it inevitably diminishes in value.

At one level it could be rational for a particularly active investor to invest a small portion of their investments in volatile speculative bubbles such as bitcoin and GameStop, provided that they rebalanced their exposures regularly (i.e. taking money out whenever they experienced gains), and provided that they were confident that these speculative investments weren’t highly correlated to the rest of their portfolios. Unfortunately, as the graph above demonstrates, bitcoin fails on this second test, because its price history shows that the price of bitcoin is highly sensitive to the level of equity markets.

The Ethics of Bitcoin

Increasingly, investors in New Zealand and elsewhere are choosing to avoid having their portfolios invested in activities that they regard as unethical. They avoid investing in companies that manufacture things like tobacco products or various nasty forms of weapons.

A large part of the reason for excluding such investments is the perception that buying those companies’ shares could directly or indirectly assist them in carrying out their unsavoury activities. A counter-argument to these ethical exclusions can be that many of these companies will continue to go ahead with their undesirable activities regardless of whether some shareholders sell their shares. This counter-argument will often be true up to a certain point, but if enough shareholders sell out of a company, it seems reasonable to expect that a lower share price will start to affect how it conducts its operations.

Generally, high share prices “tell” company boards and management that shareholders like what they’re doing, and are happy for the companies to keep investing more money in whatever they do, whereas weak share prices leave company management worried about takeover bids, and force them to consider whether company resources might be better channelled into buying back shares rather than expanding their operations. Hence, avoiding certain companies on ethical grounds is likely to help in at least some minor indirect ways to reduce how much those companies invest in unethical activities.

However, with bitcoin, I would argue that there is a far more direct relationship between how much you invest in bitcoin and the financing of unethical activities. For every dollar a punter invests in bitcoin, an existing bitcoin holder is able to take their money out, and a lot of existing bitcoin holders have ended up owning bitcoin because they engaged in activities that were so dodgy that they could not risk the traceability of being paid in cash.

While the financial statements of many companies most commonly excluded on ethical grounds suggest that every dollar that investors avoid investing in these companies likely makes less than a cent of difference to how much they invest in their operations, I would suggest that for each dollar invested in bitcoin, there is a real risk that 20 or 30 cents might flow to dodgy characters engaged in particularly unethical activities. Aside from the financial risks of investing in bitcoin, people should consider their consciences before buying bitcoin from unidentifiable counterparties. The dodgy characters who use bitcoin to avoid detection would struggle to get their money out if were not for the widespread participation of speculative investors.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios that include shares in companies that are involved in the mining of gold.

On the face of it, Bitcoin has only just enough global capacity to handle the peak electronic transaction demands of a city like Tauranga