How Passive Decisions Affect Investment Markets

NBR Articles, published 6 October 2020

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall, originally appeared in the NBR on 6 October 2020.

Globally, a greater proportion of investors’ money is now being invested in passive funds than ever before. When investors place money in these funds, the key investment decision is the investors’ decisions about which funds to invest in, as the funds themselves essentially operate on auto-pilot.

Passive funds aim to replicate the performance of a benchmark index, by investing in the securities that make up that index. With the largest passive funds achieving expense ratios of less than 0.1%, investors in these funds can anticipate returns that will come very close to the return of market or market sector represented by the fund's benchmark index.

It is easy to understand why exchange traded funds (“ETFs”) and other passive vehicles make sense for investors who compare them to the alternative to paying fees of over 1% per annum for active management. Investors are increasingly aware of studies such as SPIVA (“S&P Indices Versus Active”) which show that the vast majority of fund managers have failed to achieve long term returns that exceed the return of benchmark indices by a sufficient margin to pay for their fees. Conveniently, ETFs also work well for financial advisors and multi asset class fund managers who want to clip the ticket for getting their clients diversified exposure to global equity markets without having to do too much work!

The theoretical support for passive investment is also strong. The pricing of investment markets reflects the combined wisdom of thousands of often very intelligent investors with very similar objectives, who are all competing to identify investment opportunities that others haven’t recognised. This competition for investment opportunities makes it intrinsically difficult to consistently achieve investment results that are much better than the average. And any investor who may (quite rationally) have doubts about their ability to achieve above-average results can quite simply opt out of this competition by investing in a passive broad market fund and therefore achieve investment results that will by definition be quite close to the average performance achieved by all the smart minds on Wall Street.

Because passive investment aims to replicate a broader market, it can be natural to assume that passive investment funds are spread fairly evenly across all companies in rough proportion to the number of freely-traded shares that each company has on issue. If this were the case, then we would not expect passive investment to have much effect on the relative pricing of different equities, because passive investment would be simply boosting demand for all equities in equal proportion.

However, passive investment funds are not spread evenly across the market. Some companies clearly have a very large portion of their share capital held by passive or mechanistic funds, while other companies are barely touched by passive investment. There are two key reasons for this:

- Knowingly or otherwise, “passive” investors are making active investment decisions by choosing which passive investment vehicles to invest in. Only a small proportion of funds flowing into passive investment vehicles is invested in broad global market equity funds that cover large and small companies across all geographies and sectors. Instead, most passive money is invested in funds that are limited to either: a single geography (particularly the United States); a single sector (e.g. technology or real estate investment trusts); a particular characteristic (e.g. value, growth, quality, or low risk); or a particular range of capitalisation (e.g. large, mid, or small capitalisation companies).

As a general observation, it seems that when retail investors choose to passively invest in a particular sector this is generally a “trend-based” decision motivated by an observation that a particular sector has been achieving strong growth, with very little consideration paid to the valuation of the sector. By contrast, retail investors are often bargain hunters when looking at individual stocks. Consequentially, the shift of retail investor focus from picking stocks to selecting ETFs could be one factor contributing to the strong performance of growth stocks over recent years. - Passive funds follow benchmark indices, which each have their own specific criteria for determining which stocks are included in the index and how they are weighted. Individual criteria range from sensible to bizarre, but for each benchmark index there is inevitably the need to draw some boundaries, which can result in vastly different levels of passive demand for companies that fall on each side of an index’s boundary criteria. The ability of index inclusions to influence a company’s share price was seen dramatically last month when the valuation of Tesla rose by tens of billions of dollars based on speculation that Tesla would be added to the S&P 500 index, then fell by a similar amount when it was not added to that benchmark.

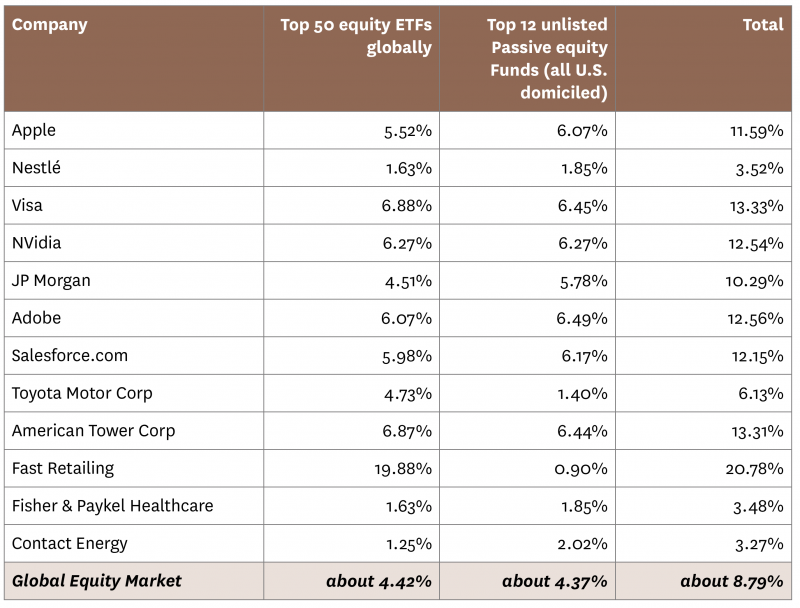

We can get a sense of how these factors affect passive demand by simply looking at what proportion of different companies’ share capital is held by a range of large passive funds. For the table below I have looked at the stock holdings for each of world’s 50 largest ETFs and for each of the 12 largest unlisted passive funds that I could identify[1].

Proportion of selected companies owned by the largest passive funds

[1] The data in this table is based on regulatory filings or disclosures by the funds themselves, sourced through Bloomberg.

From this table it seems clear that (in aggregate) passive funds generally hold a larger proportion of US equities than they do of equities in other parts of the world. This seems to be because investors in the United States have far more appetite for US-specific passive funds than global passive funds, whereas investors outside of the US don’t just focus on their local markets – they also have a strong appetite for global funds and even US-specific funds.

More subtly, passive funds own slightly higher proportions of companies in certain sectors (notably technology and real estate investment trusts) than they do for companies in other sectors. This is mainly due to the popularity of ETFs focussed on these specific sectors, but it is also partly due to the popularity of ETFs tied to “growth” and “dividend” indices.

It is important to appreciate that the table above only tabulates the shares held by the largest passive funds, and that the total passive ownership of most companies on this list will be significantly higher than shown in the table. For example, two Blackrock (iShares) Clean Energy ETFs have a combined holding in Contact Energy of 3.7%, but these holdings were not included in the table above as neither of these ETFs came close to making the list of the top 50 ETFs.

Fast Retailing (the Japanese company that owns the Uniqlo clothing brand) stands out as the company on the table that has the highest proportion of passive ownership. This is due to the bizarre rules for the construction of the Nikkei-225 index, which is used as a benchmark for three of the world’s 50 largest ETFs. The Nikkei-225 follows a theoretical investment strategy of owning one share each in 225 different Japanese companies. As Fast Retailing has the highest share price of any of these companies, it gets the largest portfolio weighting in the ETFs that follow the Nikkei-225, resulting in inflated passive demand for its shares.

How is ETF demand affecting prices?

To what extent do differences in the passive demand for different companies’ shares effect their share prices? Clearly, a shift in passive demand for a company’s shares needs to be balanced by an equal and opposite shift in active investors’ demand for the same shares.

Hence, the impact that ETF demand has on share prices depends on how many more shares would active investors buy if the share price fell by (say) 1%, or how many shares would they sell if the share price rose by 1%. In my view, this price elasticity of active investor demand is lower than it has been in the past, for a few key reasons:

- As a direct result of an increasing proportion of equities being managed passively, there is now a lower proportion of equities being managed actively, which means that active managers in aggregate have less “fire power” to accommodate passive demand.

- As growth has outperformed value, a higher proportion of total equity funds are being managed by growth-focussed fund managers rather than value-focussed fund managers, and investors who focus on growth companies typically to tend to respond less to changes in share prices than value-focussed investors.

- Active investors tend to be more willing to respond to changes in share prices when they have a close substitute that they can buy to replace whatever stock they are selling into passive demand. As active investors sell stock over time to accommodate passive vehicles that are chasing particular sectors or themes, they find that all the substitutes that they might buy to accommodate one line of selling are being bid up at the same time, and therefore run out of capacity to keep selling similar stocks. My sense is that the active investors who may have previously sold stock to satisfy the demand of passive investment vehicles may be now running out of inventory in many “hot” sectors, themes or geographies that are being favoured by many passive vehicles.

The influence of passive investment on share prices can be seen around the world in many cases where two securities linked to the same underlying source of income trade at quite different prices because of different treatment in benchmark indices. For example, some companies have two classes of shares that are both entitled to the same dividend, but with only the more liquid of the two securities included in benchmark indices.

In other cases, the vast majority of the value of a listed holding company relates to the shares it owns in another listed company, but only one of these companies is included in commonly-followed benchmark indices. In many of these cases, the security that is included in the benchmark indices is trading at or near record premiums above the price of the security that is excluded from benchmark indices.

NZ precedent

Although the current level of demand for passive investment vehicles is unprecedented on a global scale, in New Zealand we are privileged to have been through this experience in the past. In the early 1990s, the Inland Revenue Department interpreted tax law as requiring capital gains taxes to generally be paid on capital gains realised within active managed investment portfolios, but deemed that gains realised in passively managed portfolios would generally be exempt from such taxation.

This resulted in a seismic shift in the local funds management environment as local pension funds and other investors took their money away from active managed investment mandates in favour of passive investment management. This shift from active management into passive management reached a peak in about 1996, boosting the share prices of New Zealand companies that were well-represented in benchmark indices, and leading to a dearth of demand for shares that were unrepresented in those indices.

The subsequent experience should be encouraging for those of us who persist with the out-of-favour art of active management: the 10 years following this 1996 peak in passive investment were a golden age for active management, with pretty much every active manager of NZ Equities outperforming their passive counterparts. While investors who put their money into passive NZ equity funds in the mid-1990s managed to achieve a return that roughly matched the return on the imperfect benchmarks that they chose to follow, investors in actively managed funds got a significantly better pre-tax return.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios that hold shares in Apple, Nestlé, Visa, JP Morgan, and Toyota Motor Corp, and the writer personally holds shares in Fisher & Paykel Healthcare.

Because passive investment aims to replicate a broader market, it can be natural to assume funds are spread fairly evenly. However, some companies have a large portion of their share capital held by passive funds, while others are barely touched by passive investment.”