Why Higher-Risk Doesn't Pay Off In Equity Investing

NBR Articles, published 9 March 2021

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall, originally appeared in the NBR on 9 March 2021.

One of the basic tenets of finance theory is that because investors prefer to reduce uncertainty about future investment returns, they will demand higher returns from riskier investments. From this starting point, finance theory predicts investors’ preference to reduce risk will affect the pricing of investment markets in such a way that we should expect to find that riskier investments typically produce higher returns over the longer term.

In the real world, the prediction of higher returns to riskier investments is only partially supported by long-term data. The theory fits pretty well with the long-term returns that investors have received from different asset classes (listed equities, bonds, property, etc). Amongst asset classes, there is clear evidence that returns from riskier asset classes such as equities have been higher than returns from less risky asset classes such as bonds over long time periods.

But when we zero in on the equity market to find the relationship between the risk and return of individual equities, the predictions of finance theory appear to have gone a little awry. Several empirical studies have failed to find a long-term positive correlation between risk and return within the equity market. This result appears to hold up regardless of whether researchers measure risk in terms of volatility or beta, and it cannot be fully explained away by taking account of other factors. Some studies have concluded that lower-risk (“defensive”) equities have outperformed higher-risk (“cyclical”) equities over the longer term while other studies fail to find a statistically meaningful difference. As far as we can tell, no studies find that riskier equities have historically out-performed lower risk equities to the extent that would be predicted by finance theory. Further, it seems that outperformance of defensive equities compared to higher risk equities is more attributable to higher-risk equities underperforming medium risk equities than it is to any difference between the returns of lower-risk equities versus medium risk equities. In short, there is ample evidence that investors have not enjoyed a good long-term reward-for-risk from investing in equities that are particularly volatile or sensitive to market conditions.

If it continues into the future, the observation that lower-risk equities offer similar or higher long-run returns to higher-risk equities would seem to be something of a free lunch for investors. Investors could shift the portion of their portfolios that is invested in higher-risk equities into lower-risk equities and anticipate the same return for less risk. And if they are more interested in higher returns than lower risk, then they could simply hold more equities to counter the fact that the equity component of their portfolio is less risky (such that if they got the balance right, they should end up with higher returns for similar risk).

Why do lower-risk equities do so well over time?

Why have lower-risk equities historically produced better risk-adjusted returns than higher-risk equities? Logically, a class of investment can only produce superior risk-adjusted returns over very long periods if investors (or their agents) have tended to systematically under-value it. There are a number of possible explanations as to why investors and fund managers may tend to systematically under-appreciate lower-risk equities and over-appreciate riskier equities. I suspect that many of the following explanations contribute to a systematic under-appreciation of lower-risk equities (and/or an over-appreciation for higher risk equities):

- There is evidence that analyst forecasts (and therefore return expectations) tend to be over-optimistic for companies where there is a wide range of possible future outcomes (as proxied by either a wide dispersion between different analyst forecasts or from historic variability in profitability). Companies with a wide range of possible future trajectories tend to be higher than average risk. Conversely, analyst forecasts tend to be closer to the mark for “boring” companies that produce similar outcomes each year, and such companies tend to be of lower-than-average risk.

- It seems that (intentionally or otherwise) many investors are naturally extremophiles, tending to invest a disproportionate share of their portfolios in companies that attract their attention for reasons such as large price movements in either direction, a lot of media coverage, extremely rapid growth, or extreme value characteristics. Data from Robinhood (a US equivalent of Sharesies and Hatch) shows that their retail investors tend to skew towards volatile companies that sit at either extreme of the value-growth continuum. For example, the current list of top ten Robinhood holdings currently include both Tesla and Nio, electric car specialists that are both valued at more than 10 times forecast sales and more than 100 times projected operating profit due to their blue sky potential, but it also includes Ford, an internal combustion diehard trading on less than a third of annual sales, and AMC Entertainment, a movie theatre chain that is bleeding cash while Covid-19 keeps people away from movie theatres. I would argue that investing in companies with extreme characteristics that attract a lot of attention is a natural tendency for many novice investors. More experienced investors can also fall into this trap if we are unaware of the danger or are undisciplined in our investment approach. Companies that are extremely cheap or which have been growing extremely rapidly tend to be more volatile and more sensitive to market conditions than "Goldilocks" companies that sit somewhere in the middle of range in terms of valuation and growth characteristics.

- Some investors are far more focussed on maximising return than managing risk, and they accordingly pay little attention to risk characteristics when they’re evaluating investments. If these investors have a significant influence on market pricing, they could create an environment that allows other investors to select for low risk without sacrificing return.

- Many fund management companies (and their employees) are evaluated (and receive performance related pay) almost entirely on the basis of the returns they achieved, and not at all on how much risk they took to achieve those returns. This leads to many fund managers tending to inch slightly up the risk spectrum in the hope of achieving better returns. When I've looked at databases of global fund manager returns in the past, it has been clear that the majority of equity fund managers hold portfolios that tend to be slightly more sensitive to market conditions than their benchmark indices (although it must be said that equity fund managers are more disciplined than fixed interest managers in this regard – it is extremely rare to find a fixed interest manager who is not taking significantly more credit risk than their benchmark index).

In my opinion, none of these factors are any less relevant today than they have been in the past.

The relative performance of lower-risk equities swings around over time.

Of course, the fact that lower-risk equities have historically produced a better reward-for-risk than higher-risk equities does not mean that it will occur in every single year. In fact, the past year has been about the worst period in history for the relative performance of lower-risk investing.

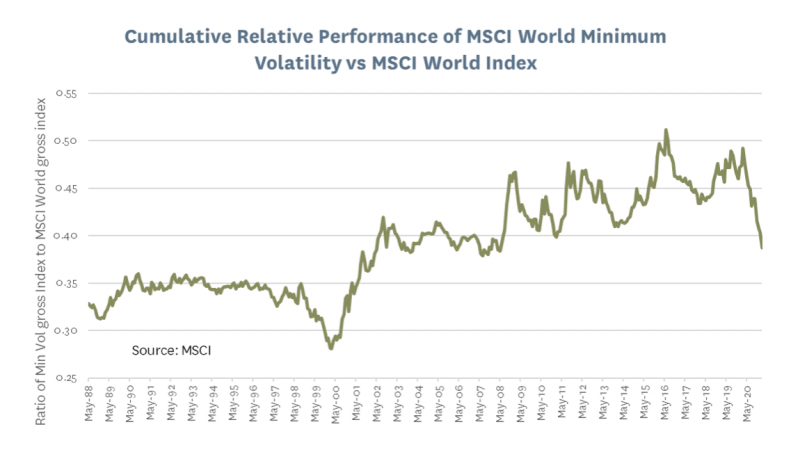

This can be seen in the graph below, which charts the cumulative performance of MSCI’s Minimum Volatility World index (which is designed to favour lower-risk stocks) in relation to the performance of the MSCI World Index. While the broad upward slope of the graph shows that lower-risk stocks have outperformed the broader (developed market) universe over the entire period, the saw-toothed shape of that slope shows that the relative performance of lower-risk stocks can swing around quite a lot over periods of 1 – 3 years, and lower risk stocks have shown a particularly sharp under-performance over the last 11 months of the graph.

If you examine this graph closely, you may also observe that it is rare for lower-risk stocks to continue either out-performing or under-performing the broader market universe for much more than 3 years. In fact, when we examine the data, we find that there is a (quite significant) -0.46 correlation between the relative performance of the Minimum Volatility index in one 18-month period and its relative performance in the subsequent 18 month period. On the face of it, this historic tendency for the relative performance of low-risk stocks to “mean-revert” (i.e. reverse much of their previous relative performance) implies that the significant underperformance of low-risk stocks over the past year may be setting up a good environment for lower-risk stocks to outperform over the next one or two years.

No evidence that equity markets are currently paying a premium for lower risk characteristics

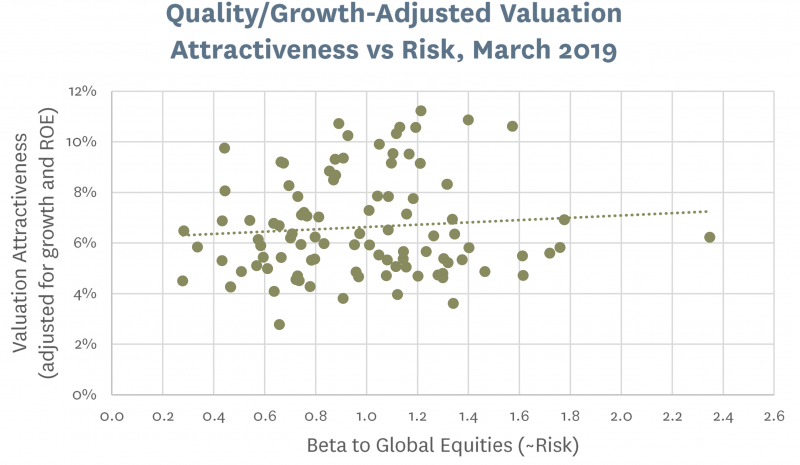

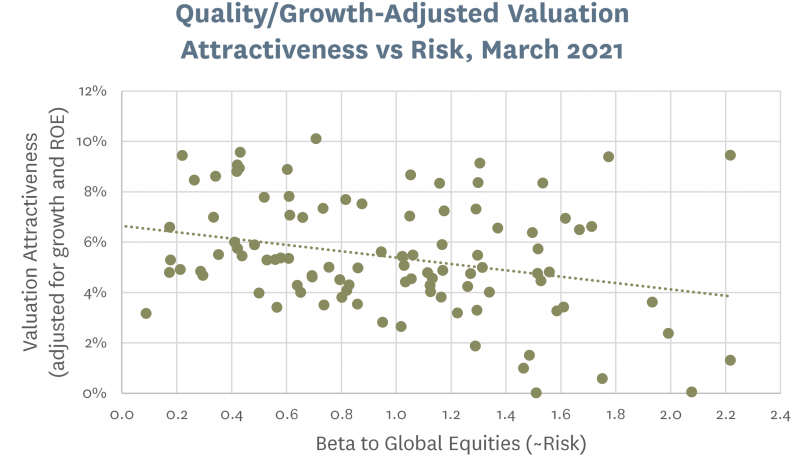

The conclusion that lower-risk equities may be due for a period of outperformance is supported if we look at the relationship between risk and valuation that seems to be currently priced into the equity market, and compare this to how it looked a couple of years ago. In the graphs below we have plotted the beta (a measure of risk) for each of the 100 largest companies in the MSCI World index against a composite valuation measure that takes account of growth and return on equity as well as various valuation metrics. If you look at the graph from two years ago, you can see that there appeared to be a slight positive relationship between valuation attractiveness and risk, indicating that in 2019 the market was generally pricing riskier companies to deliver slightly higher returns than lower-risk companies. But if you look at the graph for today (March 2021) you can see that this relationship has reversed – riskier stocks now seem to be priced to deliver lower returns than is the case for more defensive stocks.

These graphs should be not seen as conclusive, as they rely on a combination of backward-looking and consensus-based measures of valuation attractiveness and a backward-looking measure of risk, and neither of these will be perfect predictors of the future. Simple valuation metrics may currently be less reliable than normal, due to the different ways in which the covid-19 pandemic has affected earnings from different companies.

Backward-looking measures of risk have generally worked reasonably well as forward-looking measures of risk, but there are always a few exceptions. For example, some Information Technology companies that had historically been very sensitive to market conditions suddenly turned into good diversifiers in 2020 when Covid-19 struck and people around the world suddenly began working from home and practicing social distancing (resulting in huge demand for the products of certain IT companies).

Although these graphs are imperfect, their broad conclusion is similar to what we have been observing in global equity markets over the last few months. It seems very apparent that in many cases investors have been chasing after volatile stocks that tend to swing around with market sentiment, whilst abandoning "boring" stable companies in sectors like Consumers Staples, Health Care, and the Utilities sector. (These have been the 3 worst performing sectors so far in 2021).

Influence of bond yields

The rise in global bond yields over the past few months provides some justification for the recent underperformance of lower-risk sectors of the equity market. Bonds are more similar to lower-risk equities than they are to higher-risk equities, so it makes sense that the share prices of lower-risk equities should be more sensitive to rises in bond yields. However, some of the companies that are most sensitive to market conditions are those that are trading on high price/earnings multiples, which implicitly price in a lot of future growth. In theory, the valuation of these growth companies should also be very sensitive to interest rates.

The author is biased!

While the comments section after my previous NBR articles has sometimes attracted accusations of self-interest when I've ventured opinions on subjects such as bitcoin in which neither myself nor Te Ahumairangi Investment Management have any financial interest, readers may have better reason to take a sceptical view about my motivation when I talk favourably about lower-risk investing, as Te Ahumairangi Investment Management manages global equity portfolios that skew towards lower risk equities.

There are very few active fund managers who emphasise lower-risk investing. Investors who are interested in lower-risk investing could talk to their financial advisors about various "Minimum Volatility", "Low Risk" and "Low Volatility" ETFs that offer slightly different flavours of lower-risk investing.

Subject to their investment time horizon and risk appetite, investors may also wish to review their portfolios' holdings in companies that are volatile, leveraged, sensitive to economic conditions, or have greater than average sensitivity to the overall level of the share market. The past year has been a great environment for these sorts of companies, but (while no one can accurately predict the future) historical patterns suggest that this may not continue for much longer.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios that skew towards lower risk equities.

Many fund management companies are evaluated almost entirely on the basis of the returns… This leads to many fund managers tending to inch slightly up the risk spectrum in the hope of achieving better returns… The majority of equity fund managers hold portfolios that tend to be slightly more sensitive to market conditions than their benchmark indices