Premium On Growth Stocks Echoes Dotcom Boom

NBR Articles, published 1 September 2020

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall, originally appeared in the NBR on 1 September 2020.

By historical standards, investors in global equity markets are currently paying an extremely high premium for growth stocks.

On many valuation metrics, the multiples accorded to the most expensive cohort of large companies now exceed the multiples accorded to the least expensive cohort of large companies by a margin that is similar to the valuation premiums we saw at the peak of the tech boom that ended in early 2000.

Clearly, it generally makes sense for investors to pay a higher multiple for companies that seem to have above-average growth prospects. But what is the right price to pay for prospect of above average growth?

Over the last few years the investors who have achieved the best returns have often been those who have focussed almost exclusively on growth and paid scant regard to valuations. Does this prove that valuations never matter? No. Although paying a lot of attention to valuations can prove to be counter-productive in the short-term if market pricing shifts in the way it has over the last few years, valuations are still very important over the long term. Valuations will prove to be particularly important if market pricing reverts back to the norms we have seen in the past.

The long run return that you achieve from investing in any company will be determined not only by the growth it achieves and the amount of capital it requires to finance that growth, but also the price that you pay to buy shares in the company. All three elements are very important determinants of long run return, but it seems to be a characteristic of equity markets to periodically emphasise one or two of these elements at the expense of the other(s).

If you pay too high a price for a stock it becomes mathematically difficult for it deliver a good return to you as an investor, even if it achieves a long period of exceptional growth in earnings and cashflow. At some point in the future, each rapidly growing company is ultimately going to reach a point of maturity from which it can no longer grow any faster than the average company.

When the market recognises that this is happening, its valuation multiple will inevitably fall to something close to the average of the broader market.

Long term investment returns for equities come from the combination of cashflow (e.g. dividends) and growth. As investors generally demand long term returns from equity investments that are significantly higher than the trend rate of growth in the broader economy, there is an implicit need for companies that are only achieving average levels of growth to pay sufficient dividends (or other cash) to close the gap between investors’ return expectations and the company’s expected growth rate. If a company facing a slow-down in growth is unable to sustain a high enough dividend to meet investors’ expectations, then the share price can fall until the ratio between dividend and share price meets investors’ expectations!

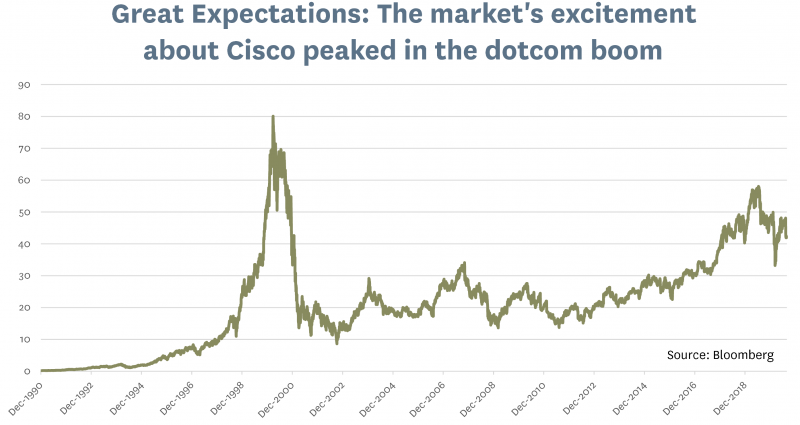

We can see how this can play out by looking at some of the darlings of the previous big technology boom (i.e. the “new era” tech boom that ended in the year 2000). Back then, Cisco was one of the largest technology companies and was regarded as having some of the best growth prospects. In July 2000, the market valued Cisco’s business at US$443 million, representing 23 times trailing revenues and 96 times trailing EBIT. This valuation was broadly similar to how the market now values current market darlings like Tesla, salesforce.com, Nvidia, and Xero.

So how did investors do out of investing in Cisco? In one sense, they were right – Cisco did continue to grow. Over the 20 years since 2000, Cisco has tripled its operating profits and quadrupled its profit after tax. Today it is the 5th most profitable IT company in the MSCI World index. But returns to investors in Cisco have been disappointing. Even after reinvesting their dividends in the stock, investors in Cisco shares would still be 22% poorer than they were in July 2000 (a compound return of -1.2% per annum). The reason for this poor performance is that as Cisco’s growth prospects have become more ordinary, so has its valuation multiple, and the decline in its valuation multiple has offset the growth in its earnings.

But what about the really big winners, companies like Microsoft and Apple, which have grown to be the most profitable privately owned companies in the world? Surely if you got in early enough to either of these companies, returns would have been fantastic regardless of what price you paid? Not quite. Looking back 33 years to August 1987 (the earliest date for which I could find good fundamental data), an investor in Microsoft would have achieved returns* of 22.5% per annum, while an investor in Apple would have achieved returns* of 18.8% per annum. But back then, investors were paying relatively modest valuation multiples for these two companies, which had a lower aggregate valuation in August 1987 than companies like Xero or Fisher & Paykel Healthcare are individually valued at today. In August 1987, the market was valuing Apple on an enterprise value of 10 times forward-looking EBIT and was marking Microsoft at just under 16 times forward EBIT. How good would the long-run returns have been if investors had paid similar multiples for Microsoft and Apple in 1987 as they are prepared to pay for companies like Nvidia, salesforce.com, Tesla, and Xero today? By my calculation, if investors had bought Microsoft and Apple on prices that implied and enterprise value of 100 times EBIT in 1987, the returns* they would have achieved over the subsequent 33 years would have been still good, but less spectacular, at 17.7% for Microsoft and 10.9% for Apple.

* For these calculations I use Internal Rates of Return (IRRs), a cashflow measure of return that is not affected by assumptions about how dividends are re-invested.

While any sort of double-digit return looks fantastic from the starting point of today’s near-zero interest rates, it seems unlikely that companies like Nvidia, salesforce.com, and Tesla could all achieve growth rates from today’s levels that are comparable to what Microsoft achieved between 1987 and 2020. In 1987, Microsoft had annual revenues of just US$345 million (markedly less than Xero is achieving today). By contrast, Nvidia, salesforce.com, and Tesla are each already achieving over US$10 billion of revenues. To achieve compound growth that is anywhere near as significant as what Microsoft has achieved would be an incredible feat, as it would imply that in the future they will each be vastly more dominant than Microsoft is today.

While it is quite likely that there may be one or two companies amongst the current crop of market darlings that ultimately grow to enjoy the sort of market position that Apple and Microsoft enjoy today, it is no easy exercise to pick which one will be most successful.

A lot of the money that is flowing into the highly valued tech names today is not even trying to pick the winners. It is arriving in the sector through ETFs and other funds that invest across the entire sector. While such an approach will probably result in some exposure to the future winners, it will inevitably also result in a lot of exposure to future duds. Analysis by (the appropriately named) Empirical Research Partners identifies “big growers” each year (based on favourable growth/quality characteristics) and looks at how these companies tend to perform over subsequent time periods. Their analysis shows that only a minority of “big growers” continue to sustain significant double-digit growth, and that a fair number fail completely or shrink to obscurity. Anyone allocating money to growth stocks or growth sectors ought to be cognisant of the risk that many of the underlying investments are likely to disappoint. They should be wary about investing at valuations that implicitly assume that the vast majority of past growers will continue to grow and gain market share.

Market history shows that the premium that investors are prepared to pay for growth varies significantly over time. Investors have paid peak premiums for growth characteristics in the early 1970s, 1999/2000, and today. At the other extreme, market prices embedded very little premium for growth in the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s. MSCI maintain “value” and “growth” indices dating back to 1974, which can be used to roughly gauge how returns from value-seeking investment strategies have compared to returns from growth-seeking investment strategies through time. Over the full period the MSCI value index has outperformed the MSCI growth index, but the important observation may be that timing matters. Returns from growth investing have been particularly poor from starting points that corresponded with markets pricing in a high premium for growth (namely 1974 and 1999/2000), but have been very good from starting points that corresponded to investors paying very little premium for growth (such as 1996 or 2006). Current market pricing looks more like 1974 and 1999 than 1996 or 2006.

Acolytes of growth-focussed investing will no doubt push back against the argument that growth stocks are currently expensive, by making the valid point that the current environment of low interest rates lifts the appropriate valuation of growth companies more than other companies, as it means that we should apply less of a discount for cashflows that are due to flow to investors a long way into the future. However, current valuations of growth companies imply that most of what we are paying for when invest in these companies are the cashflows that they are expected to generate more than 20 or 30 years into the future. While it seems likely that the global economic and policy environment will keep interest rates low for the next 4 or 5 years, it is not obvious to me that this necessarily implies that interest rates will be any lower than their historical average 20 or 30 years into the future.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios that hold shares in Microsoft, Apple, and Cisco.

A lot of the money that is flowing into the highly valued tech names today is not even trying to pick the winners, it is arriving across the entire sector. While this will probably result in some exposure to future winners, it will inevitably also result in a lot of exposure to future duds