Quality – one man’s trash, another man’s treasure

NBR Articles, published 25 February 2025

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Senior Equity Analyst Jack Crowley,

originally appeared in the NBR on 25 February 2025.

It is important to distinguish between high-quality and low-quality companies

When picking stocks solely on quantitative criteria (such as valuation or growth rates), there is a danger that strong returns fail to materialise. For example, even if a company trades on a cheap multiple of earnings, profits may have been overstated (or may not be sustained); these earnings may not translate to actual cash; or the company may invest in unproductive areas. Similarly, for a company that has been achieving strong growth, growth may stall (particularly if cyclically driven) or excessive investment may be required. As a result, fundamental investors typically use a range of qualitative assessments and weigh various risks; quantitative investors often seek to distinguish between high-quality and low-quality companies using composite scores of a number of “quality” metrics.

The track record (and elusive nature) of quality merits further investigation

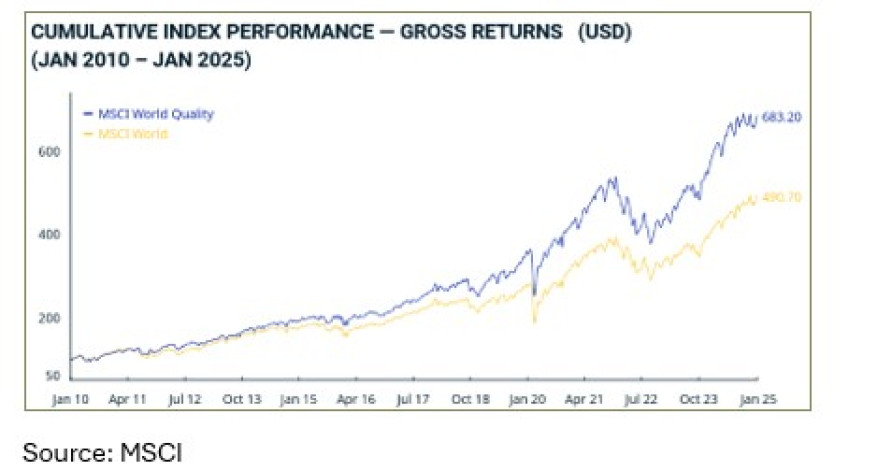

Over the long term, many quality indices have performed strongly. As illustrated below, the MSCI World Quality index has convincingly outperformed the broader equity index. This result is generally mirrored elsewhere (including long-short approaches such those produced by Citi). However, different investors (and index providers) often have different approaches to defining quality; blending together multiple criteria is common – the aforementioned Citi index equally weights 6 measures. As a result, it is often surprising to see some of the stocks within quality indices, and similarly what can be found in the reject pile.

There tends to be some overlap between the criteria used to define quality

While there’s no universal definition of quality, a number of recurring themes exist (return on capital, profitability, stability, and strong conversion of reported profits into cash flows, etc.). Often some overlap appears to exist. Other things equal, a high profit margin supports a high return on capital and stabilises performance by establishing a margin buffer; when return on capital is high (i.e. profits are large to net assets) changes in net assets are less likely to result in departures between reported profits and cash flows.

Return on capital is a useful starting point to think about quality more rigorously, but fails in some situations…

For the duration of this article, I will focus on return on capital while highlighting some common measurement pitfalls which have the potential to result in ‘hidden gems’. In simple terms, return on capital tells an investor how many dollars of profit is received per dollar invested. One such measure frequently used in the construction of quality indices is return on equity (calculated as net income / equity) or “ROE”. As an example, if I created a company with an initial equity investment of $1 million and made a net profit of $100,000 this is a 10% ROE. If the profit is reinvested in additional equipment which supports subsequent profits growing to $120,000 the ROE will have improved to almost 11% ($120,000 / $1.1 million).

It would be an oversimplification to assume that the essence of quality can be distilled to a single metric. However, from one perspective, return on capital is relatively comprehensive as it can be thought of as the combination [product] of profit margins (profit/sales) and capital turn (sales/capital). As a result, it is a central part of many investors’ frameworks. For example, Joel Greenblatt’s “Little Book that Beats the Market” advocates an approach of evaluating stocks purely on the combination of earnings yield (a valuation metric) and return on equity. In contrast, many quantitative investors will use composite scores of metrics that are relatively arbitrary when viewed in isolation (such as inventory days). Intuitively, return on capital is a key consideration when determining a fair multiple of earnings a business should trade on (for companies with growth prospects, high returns result in greater incremental profits relative to the cash flow drag of growing net assets). My back-testing suggests that high ROE companies have tended to outperform over the long run (and that low ROE companies have tended to underperform), albeit by less than many multi-factor quality screens.

Profits (‘top half’ of Return on Capital)

While earnings can be distorted by any number of items, certain items frequently occur:

- Non-cash costs: For example, many companies amortise acquisition-related assets despite no ongoing reinvestment need (at times). In effect, costs are recorded as an acquirer progressively marks down the premium paid in excess of the target’s net assets. Under Japanese standards this premium (“goodwill”) is amortised over 20 years or less; US standards only allows a portion of this premium to be amortised (typically recognised as items such as customer relationships or trademarks). The company Seven & I is based in Japan but operates 7-Eleven convenience stores globally. To accelerate growth, over time, it has acquired many convenience stores and converted these to the 7-Eleven brand. Convenience stores often lease their premise and therefore only require modest levels of capital (inventory, refrigerators, etc.). In the 2024 fiscal year, Seven & I’s operating profit of 534 billion (Japanese Yen) was calculated after deducting 120 billion in goodwill amortisation; operating profits would be +22% higher without (the unusual practice of) goodwill amortisation.

- Investments: Multiple different accounting approaches can be applied to investments. Here I focus on equity investments measured at fair value. In Korea and Japan, it is not uncommon for companies to hold various investment securities. As an example, after adjusting for treasury shares (shares held in itself), Samsung Fire & Marine (a Korean insurer) currently has a market capitalisation of 17 trillion (Korean won). It holds equities of 13 trillion including 5 trillion in Samsung Electronics shares. Dividends from these holdings are modest, and capital gains are generally not included in profits as most of these securities are measured at fair value through other comprehensive income. If we were to factor in an assumption about some normalised level of capital gains (say +4%) this would result in significantly (+17%) higher profits.

- Regulated returns: This model is common for natural monopolies such as electricity networks, where overlapping assets are an inefficient use of capital, but mechanisms are required to ensure fair pricing. When analysing regulated utilities it is important to pay attention to “slow money” (asset adjustments) vs “fast money” (profit adjustment) return concepts. For example, National Grid owns and operates the electricity network in England and Wales (among other assets). Up until 2021, National Grid would quote real returns for many assets (with the inflation component of returns captured through indexation of its regulated asset base). Incidentally, the relevant measure of UK inflation for National Grid (CPIH) reached +9% in 2023 (during the Europe energy crisis)!

Capital (‘bottom half’ of Return on Capital)

In the interest of keeping this discussion high level, I will talk about capital in general terms below. Although, as a side note, I feel it is worth pointing out that it is often advantageous to focus on invested capital (sourced from both equity and debt). I have also steered clear of multi-layer adjustments (such as the capitalisation and subsequent amortisation of R&D).

- Negative capital: While somewhat counterintuitive, negative capital can be a positive valuation attribute. For example, Verisign is a provider of internet domain name registry services. In effect, it is the wholesale provider for all .com registrations. It currently receives US$10.26 per year for each top-level .com domain in existence. Verisign has negative capital as it has limited assets and receives some revenues in advance (resulting in a deferred revenue liability equivalent to ~80% of annual sales). This allows Verisign to return more than 100% of reported profits to shareholders each year (via share buybacks; increasing the proportion of ownership attributable to remaining investors). A negative return on equity is obviously undesirable if this is the result of a company reporting losses, but is positive for companies delivering strong profits without requiring capital (such as Verisign). Not all quant screens make this distinction.

- Goodwill: As discussed in the prior section, acquired intangibles sometimes have no ongoing reinvestment need. In some cases, goodwill may represent a considerable portion of capital. For example, over time Walt Disney (Disney) has undertaken a number of significant acquisitions such Pixar in 2006, Lucasfilm (StarWars) in 2012, and Twenty-First Century Fox in 2019. As a result, at the end fiscal year 2024 Disney’s equity of US$106 billion included US$73 billion in goodwill. Excluding goodwill, equity capital would be almost -70% lower (just US$33bn).

- Stale balance sheet items: As cost-based accounting applies to a wide range of balance sheet items, it can sometimes be useful to consider alternative measurement approaches (such as replacement costs or fair value estimates). At times estimates are readily available. For example, in early 2023 following a slate of bank collapses (starting with Silicon Valley Bank), my colleague (Nicholas Bagnall) wrote an NBR column discussing the issue of held-to-maturity investments, whereby banks (particularly in the US) were increasingly measuring fixed interest securities (including highly-liquid, long-term treasuries) at cost. Since many of these securities were purchased, prices had fallen substantially due to interest rate rises. In many cases, notes to the financial accounts highlighted that equity capital would be considerably lower if measured at fair value (i.e. current prices). At the time, two of the banks discussed (Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic) had negative equity capital (liabilities exceeding assets) if measured at fair value. (Unfortunately for banks this is not a desirable trait given regulated minimum capital requirement and the risk of credit losses).

To deliver the best results, subjective judgement and critical thinking is often required

As might be apparent, subjective judgements are often required. For banks, the fair value of equity capital collapsing to zero is certainly not a hallmark of quality; for Disney, it might be worthwhile considering whether large acquisitions every 5-10 years are necessary to sustain its business. I also feel it is important to mention that critical thinking is required to address a major shortcoming of seeking out high return on capital companies. Margins and returns on average tend to mean revert over time (i.e. gravitate towards average levels). This seems logical given the potential for lucrative businesses to attract competition. Furthermore, even for companies with particularly ‘wide moats’, there will be finite opportunities to grow while continuing to achieve supernormal returns. On average, these headwinds are not sufficient to undermine the appeal of a high return on capital (i.e. the efficient conversion of capital to profits). However, in my view, it is important to reflect on how likely a company is to be disrupted.

In summary, return on capital is a useful starting point for thinking about quality… while it sometimes falls short, by taking a deeper look, a number of pitfalls can be resolved

In conclusion, it is important to distinguish between high-quality and low-quality companies. The track record (and elusive nature) of quality merits further investigation. There is no universal definition for quality. As a result, the stocks within quality indices (and rejects) can sometimes be surprising (and are often inconsistent between index providers). This presents an opportunity to discover ‘diamonds in the rough’. Return on capital appears to be an important theme (within multi-factor quality frameworks) and is a useful starting point, in my view. While this sometimes falls short, there is an abundance of opportunities to improve this measure by taking a deeper look (at both earnings and capital). Some fruitful areas for adjustments include: non-cash costs, investments, regulated returns, negative capital, goodwill, and stale balance sheet items. As is often the case, for the best results, subjective judgement and critical thinking is sometimes required.

Jack Crowley is a Senior Equity Analyst at Te Ahumairangi Investment Management

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited, and an investor in the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios (including the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund) that invest in global equity markets. These portfolios hold shares in the following companies mentioned in this column: Seven & I, Samsung Fire & Marine, National Grid, Verisign, and Walt Disney.