Stock-based compensation and the Mismeasurement of Earnings

NBR Articles, published 9 November 2021

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall, originally appeared in the NBR on 9 November 2021.

Comparisons of the valuation of individual equities or entire equity markets typically start with the Price-to-Earnings ratio (a.k.a. "Price/Earnings Ratio", or simply "P/E Ratio"), which is calculated by dividing a company's share price by its earnings per share. Earnings per share is calculated as the total profits of the company divided by the number of shares on issue.

Price-to-Earnings ratios can be calculated in slightly different ways, using different measures of profits, and can be calculated off either backward looking earnings, estimates of the current year’s earnings, or estimates of earnings in future years. The way in which you measure profits can make a huge difference to your calculation of a company's P/E ratio.

Consider the table below, showing Price-to-Earnings ratios for the largest companies in the world (by market capitalisation) with December balance dates. All of these companies are US-based. In the first column, I show the P/E ratio calculated on the basis of reported earnings per share from continuing operations over the four quarters to September 2021. In the second column, I show the P/E ratio calculated based on broker analyst forecasts for earnings per share for the December 2021 financial year.

The difference between the two columns is stark, particularly in view of the fact that there is a 75% over-lap between the earnings period being shown in the first column and the earnings period being shown in the second column. On the face of it, the difference in the P/E ratios might seem to indicate that analysts expect these companies to earn an average of 38% more in the 12 months to December 2021 than they earned in the 12 months to September 2021, which would imply that December quarter 2021 earnings would have to be more than double the level of December 2020 earnings.

Broker analysts are not really this bullish about these companies' short term earnings prospects. Rather, their forecasts are high because they're forecasting full year earnings that are adjusted to exclude stock-based compensation. Stock-based compensation represents a significant proportion of total expenses for each of these companies.

The executive teams of each of the companies shown in the table pay themselves mainly in the form of stock-related compensation (i.e. employee compensation that is paid in the form of shares or options to buy shares), and many companies (but to their credit, not Amazon) discourage investors from thinking about this stock-based compensation as a "real expense", by subtracting it out of the "adjusted earnings" they use when communicating with shareholders. While the "adjusted earnings" highlighted by these companies often include some other adjustments to earnings, the main difference between accounting earnings and the "adjusted earnings" is generally stock-based compensation. Broker analysts suck up these alternate measures of profitability like a cold drink on a hot day, and typically publish price targets for each company that are based on a multiple of earnings excluding stock-based compensation.

I am yet to see a coherent argument as to why investors should routinely add back stock-based compensation when trying to determine a company's ability to deliver value to shareholders. Paying employees with share certificates transfers wealth from shareholders to employees just as clearly as paying them in cash, as it means that over time, the original shareholders end up owning a smaller and smaller slice of the underlying business.

Stock-based compensation is rarely a one-off expense. Companies that shell out a lot of stock-based compensation in one year typically continue to dispense a high level of stock-based compensation in the following year, and the year after that, and so-on.

The stock-based compensation expenses reported by companies under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles ("GAAP") are calculated using modelling that tries to take account of uncertainties such as the proportion of employees who will stay longer enough to see their stock vest, and uncertainties about the performance targets required for stock to vest to employees.

Although one can argue about the details of how companies calculate the cost of stock-based compensation, my experience has been that over the fullness of time, reported stock-based compensation expenses often seem to under-estimate the true cost to shareholders of issuing stock to employees.

Amazon

For example, consider Amazon. Since the end of 2016, Amazon has issued 29.98 million shares to employees (worth US$105.5 billion at last Friday's closing price), for which it has received just US$1 million of cash and has recognised a total stock-based compensation expense of US$34.69 billion. Looking at how many shares were issued to employees in each year, I calculate that if (instead of issuing these shares to employees each year) Amazon had simply sold the same number of shares at market prices at the end of each year, it would have received aggregate proceeds totalling US$61.49 billion. In other words, the true cost of paying employees with share certificates appears to have been US$61.49 billion.

On the face of it, Amazon's recorded stock-based compensation expense seems to have under-estimated the true cost to shareholders by a total of $26.8 billion. While sell-side analysts have discounted stock-based compensation to calculate that "adjusted earnings" for Amazon over this period that are more than 50% higher than reported by Amazon under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles ("GAAP"), an alternative calculation that simply equated stock-based compensation to the value of new shares issued to employees each year would determine that Amazon's aggregate profitability has been 40% lower than reported under GAAP.

This conclusion is not just the result of Amazon's share price having risen over time. If I value the shares given to Amazon employees based on the share price at the start of each year, I calculate that the effective cost to shareholders of stock awards to employees has been $45.7 billion, $11 billion greater than the expense recognised in Amazon's accounts. I have seen similar results when I've looked at the stock-based compensation of other companies.

Investor blindness to stock-based compensation

Like the sell-side analysts that advise them, it seems the average investor in the US share market is quite happy to disregard stock-based compensation, and buy companies based on valuation multiples applied to earnings before stock-based compensation. This can be seen in the fact that many of the US companies that pay the most stock-based compensation to employees (when measured in relation to their profitability) are trading on the highest multiples to earnings, even when those earnings are grossed up to exclude stock-based compensation. Companies that dispense a lot of stock-based compensation and trade on high earnings multiples include Tesla, Nvidia, salesforce,com, Paypal, and ServiceNow.

Implications for US sharemarket vs the rest of the world

Stock-based compensation is far more prevalent in the United States than in most other countries. This means that inter-country comparisons using earnings that don’t allow for stock based compensation will tend to make the US equity market look less expensive relative to other share markets, particularly Japan, where stock-based compensation is exceedingly rare.

In the table below, we compare the P/E ratio of the US equity market with the P/E ratio of the Japanese equity market, using two different measures of earnings. The first column shows the P/E ratio calculated based on reported earnings over the 4 quarters up to the most recent reporting date (for most companies this will be the 4 quarters to September 2021), while the second column uses estimated earnings for the current fiscal year (this is the year to December 2021 for most US companies, and the year to March 2022 for most Japanese companies). The P/E ratios shown in the first column are based on earnings that are calculated after deducting stock-based compensation expenses, but it seems that the earnings estimates (surveyed by Bloomberg) used for the ratios in the second column generally do not deduct stock-based compensation expenses.

Clearly, the US sharemarket looks significantly more expensive relative to Japan if we measure earnings properly, by deducting out stock-based compensation expenses. Ignoring stock-based compensation could be supporting an illusion that the valuation of the US share market is not that much higher than Japan’s.

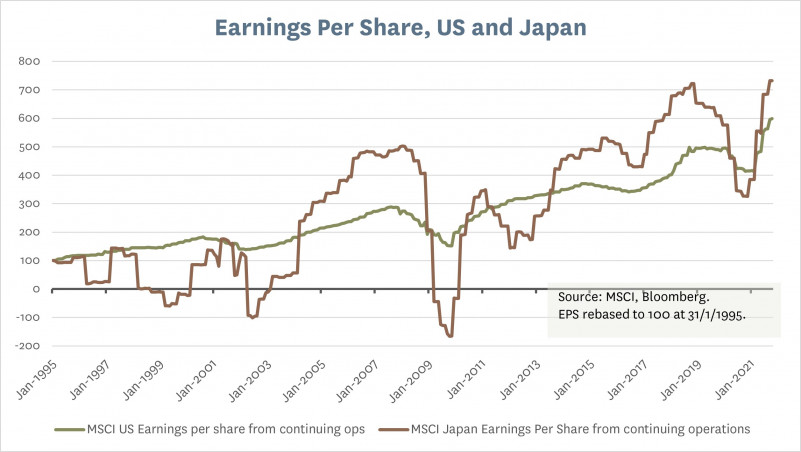

Ignoring the growing use of stock-based compensation may also be supporting an illusion that US earnings per share are growing faster than in other countries. In the graph below, I compare earnings per share for Japan and the United States, for the longest period that I can obtain trailing earnings data for the MSCI indices in each country. While Japanese earnings were volatile in the early years (due in large part due to write-offs associated with the fallout from Japan’s own equity market bubble in the 1980s), they have grown slightly faster on a per-share basis that the earnings of US companies.

While many US companies have been merrily diluting their existing shareholders by issuing shares to employees, Japanese companies have been quietly buying back their own shares. Nine of the ten largest Japanese companies have reduced their share count over the last five years, and the sole exception (Hitachi) has only increased its shares on issue by 0.2%. While many large US companies have also been steadily buying back their own shares, the average is destroyed by market darlings like Amazon, Tesla, and Nvidia that keep issuing more shares to employees.

Broker analysts suck up alternate measures of profitability like a cold drink on a hot day. I am yet to see a coherent argument as to why investors should routinely add back stock-based compensation