The Curse Of September

… and the challenge of interpreting empirical evidence

NBR Articles, published 31 August 2021

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall, originally appeared in the NBR on 31 August 2021.

With this column due to be published on the last day of August, it is perhaps timely to discuss how poorly global equity markets have historically fared in the month of September.

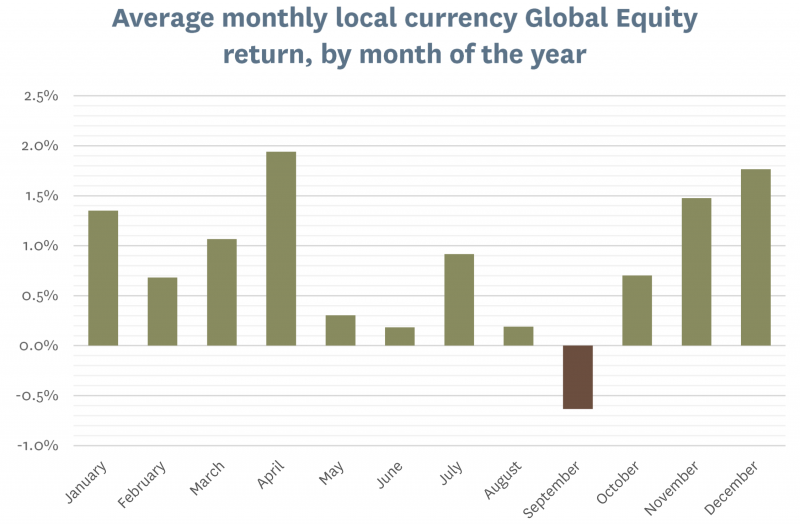

September has historically been a lousy month for global equities. While average returns from global developed equity markets have been positive (in local currency terms) in every other month of the year, the average local currency return from global developed market equities has been -0.63% over the past 51 Septembers (I only have access to good monthly return data back to 1970). This (monthly) return is 1.6% worse than the average return over the other 11 months.

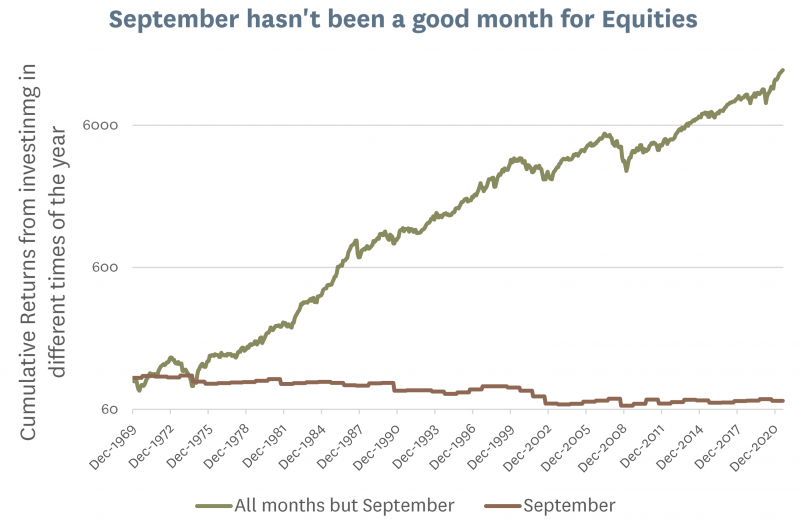

From another perspective, we can see from the next graph that a strategy of investing in global equities for 11 months of the year and putting your money under the mattress in September would have achieved a cumulative gain of 14600% over the past 50 ½ years, whereas the opposite strategy of investing in equity markets each September and keeping your money under the mattress for the rest of the year would have resulted in a cumulative loss of 31%.

Bad Luck or Bad Karma?

How should we interpret this sort of data?

Was the poor performance of equities in September over the past 50 years simply "the luck of the draw"? Could it be that if we re-wound history and pressed "play" again, we might have got a completely different result, such as equity returns being higher in September than in other months?

Or is there really some underlying seasonal effect, whereby equity markets tend to face selling pressure towards the end of September? It is conceivable that there could be some underlying reason why many investors might sell equities is September. For example, bearishness could be a side effect of seasonal affective disorder (for investors in the northern hemisphere) or it is possible that certain groups of investors might face cashflow pressures around this time of year.

The case for Bad Luck

The poor returns seen in the month of September over the past 51 years are certainly within the realms of statistical possibility in a world where the dice are not loaded for or against any particular month. By my calculation, the odds against returns in September being this much worse than the average of other months is about one chance in 132.

While these odds may seem long, the odds against any other particular month being 1.6% worse than the average of all other months would also be about one chance in 132. Hence, we can conclude that even in a totally random world there is about one chance in 11 that we'd observe that the returns from at least one month of the year were about 1.6% worse than the average of the other months. These sorts of odds are not remarkable. Most of us experience several one-chance-in-11 events every day, without feeling any need to remark about them.

The logic of market efficiency also creates a presumption against the returns from any one month being intrinsically worse than the others. The logic goes that smart investors would notice the pattern of equity returns being poor in September, and would accordingly sell equities in August and buy them back in late September, and the collective impact of many smart investors doing this would boost equity returns in September.

Of course there is an inherent paradox in dismissing any apparent pattern to investment returns as being inconsistent with market efficiency, which is that if everyone else took a similar attitude, there would be no-one doing anything that would help to offset the anomaly in market behaviour.

My former colleague Paul Dyer likes to take a sceptical approach to any evidence that a particular trading rule or pattern in market behaviour would have historically produced statistically significant results, and will pull out an image of a witch doctor whenever anyone (including himself) makes such claims!

The case for Bad Karma

Whether we like it or not, we are all affected by the seasons of the year. Seasons affect how we spend our time, how we spend our money, and can have a significant impact on some people's moods. Many businesses experience significant seasonality over the course of each year, making large profits during certain periods of the year, while barely scraping by during other times of the year. And we organise our lives around the calendar. For example, the US Federal Government works on a September fiscal year, and September is one of just two months of the year when the US government typically records a monthly surplus (thereby draining money out of the rest of the US economy).

However, there is a real risk that in looking for reasons for an apparent market anomaly, we may just end up telling ourselves "Just So" stories (like Rudyard Kipling's story of how the elephant has a trunk because it had a tug-of-war with a crocodile that bit its nose) – possible explanations, but not ones that you would have thought of if you hadn't observed the anomaly in the first place.

But given the back-drop of the world being intrinsically affected by seasons, it should not be totally surprising that some investors might often find themselves selling equities at particular times of the year. And while the theory of efficient markets would predict that any such selling would be fully offset by thousands of super-rational investors swooping in to take advantage of the opportunity created by the selling, some evidence would suggest otherwise. A recent paper (Gabaix, Xavier, and Ralph) concluded that the inflexibilities affecting how many market participants can allocate between markets means that each dollar invested into or taken out of the stock market will affect the aggregate capitalisation of the stock market by about $5. This implies that the 1.6% worse-than-average performance in Septembers could in theory be caused by some investors selling equities representing just 0.32% of the total share market.

If anything, I suspect that the current structure of how people invest in global sharemarket makes market pricing even more sensitive to any incremental buying or selling than has been the case in the past. This is because relatively more money is being managed according to passive single-asset-class mandates, and relatively more money is also being allocated by retail investors, who have tendency to respond more to themes than pricing (a polite way of saying that they often buy high and sell low!). At the same time, relatively less money is being managed in actively managed multi-asset class funds, who have historically tended to take the other side when retail investor flows have pushed the market up or down.

A Bayesian Approach

Statistical tests are meaningless without context. After all, if you roll enough dice, you'll eventually see some results that achieve a certain level of statistical significance, but if you've been looking out for patterns for a long while and have no reason to suspect the dice might be loaded, then it would be crazy to assume that these patterns would repeat.

Bayesian statistics provides a way to navigate around this issue. You think about what probability you'd have assigned to a market behaviour being "real" before you spotted the data anomaly, and then think about how the empirical evidence changes the odds. For example, if we had started with the prior expectation that there would be one chance in a hundred that returns on some of the months of the year will tend to be significantly worse than the average of the other months of the year, we could reason that:

- Even if weren't true, statistical noise means that there would be about one chance in 11 that we would expect to observe returns from one month being significantly worse than the average of the other months.

- If one month truly was destined to deliver worse returns than the others, there may be a 80% probability that we would observe (on average) this after 50 years of data.

From this starting point, we could reason that there was always:

- A 9% probability that although there was no intrinsic difference between months, we'd observe after-the-fact that returns from one month looked significant worse than the others.

- A 0.8% probability that one month was intrinsically worse and we'd see this in the data.

From this logic, it is easy to reason that there may have been a 9.8% probability that we'd observe returns from one month being as bad as we see in the data for September, but the fact that we're seeing this only indicates a 8.2% probability (=0.8% / 9.8%) that September is intrinsically worse for equities than all the others. Given our starting position that there was only a small chance that returns from one month would be that much worse than the others, the most likely explanation is still that we're simply observing statistical noise.

In this Bayesian world view, the data on poor equity performance in September elevates the possibility that one month may intrinsically be worse than the others from conceivable-but-very-unlikely to something that we might still regard as unlikely, but now looks like a possibility that we shouldn't entirely dismiss.

Incorporating possible-but-unlikely results into an investment process?

Clearly, no-one wants to base an investment approach entirely on results that might indicate only an 8.2% probability that they are backed by something real. But the reality is that many of the widely-accepted "rule of thumbs" of investing are grounded in empirical studies that are barely any more significant than our observations about returns in September.

Some investors and fund managers exclude vast swathes of the investment universe from consideration based on historical return data that doesn't come anywhere near to statistical proof. And even if you can prove that a particular investment approach would have worked in the past, how can we know that it will continue to work in the future, now that the evidence of its historic performance is available for everyone to see?

Convincing statistical proof of the benefits of a particular investment approach is extremely rare in investment markets, and we should therefore be very wary about incurring incremental costs or risks in committing heavily to investment strategies that seem to have worked well in the past. But at the same, I think it is valuable to be aware of as many empirical results as possible, and to try to incorporate these into our investment decisions if this can be done without adding to the risk of the portfolio and without incurring significant additional transaction costs.

In practice this can mean that we become quick to form prejudices against particular groups of investments, which may often be unjustified. But investment securities are not individuals, and no investor has a moral obligation to give fair consideration to every potential investment (which is a contrast to the moral obligation of an employer to avoid letting prejudices affect who they interview for a job).

For example, although there is only modest evidence that significant growth in inventories is a poor indicator of future sharemarket returns, we might choose to stop looking at a company as a potential new investment if we observe that its growth in inventories is significant in relation to reported profitability. In many cases, our "prejudice" again growing inventories could cause us to overlook a perfectly good company, but in other cases in may protect us from a potentially disastrous investment. In parallel to this logic, even though the balance of probabilities seems to indicate that historically poor share market returns in September are probably just statistical noise, the 8% probability that this may be something real means that we would be slightly more comfortable if our holdings of cash drift up by 1 or 2% in early September than we would be if the portfolio was accumulating a lot of incremental cash in early November.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited.

There is an inherent paradox in dismissing any apparent pattern to investment returns as being inconsistent with market efficiency. If everyone else took a similar attitude, no-one would be doing anything to offset the anomaly