The Forgotten Financials

NBR Articles, published 10 November 2020

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall, originally appeared in the NBR on 10 November 2020.

As a teenager new to investing in the share market in the mid-1980s, I remember having a conversation with a stockbroker who talked me out of my idea of buying ANZ shares. I had observed that they were trading at a discount to book value, and on a price/earnings multiple of just 5.5 times, but the broker expressed the view that this low multiple was well-deserved on the basis that banks always achieved lousy returns on shareholders equity. He told me that I would achieve better returns from investing in some of the leading blue-chip companies of the time, which were achieving much higher returns on shareholders’ equity.

In today’s market environment 35 years later, it is easy to envisage a consensus-hugging stockbroker giving very similar advice to a young client, with the key difference being that the high growth blue chips that they advocate would no longer include names like “Brierley Investments” and “Chase Corporation”. Although banks and other financial sector companies were held in high regard by the market prior to the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009, they are again regarded as perpetual deadbeats, doomed to forever earn poor returns on capital.

When I bowed to the consensus view that banks were deadbeats in the mid-1980s, I inadvertently missed out on investing in ANZ shares prior to a 20-year period of compound returns of over 20% per annum. Given that the consensus view was so badly wrong in 1985, it is perhaps worth asking whether markets are again being too pessimistic about the prospects for banks and other financial sector companies.

The “Financials” sector consists of banks, insurance companies, and “diversified financials” (a mixed bag of financial sector companies including investment banks, fund managers, exchanges, data providers, and brokers). In this article, I focus mainly on banks and insurers. These two groups represent the bulk of the sector, and they are similar in that they have capital-intensive business models that rely in part on earning interest on cash they are holding for their customers, and they have both been heavily de-rated by the market over the past few years.

While the Financials sector still represents the biggest share of profits in the MSCI World index (about 21% of total profits), its capitalisation has now fallen behind Information Technology and Health Care to make it just the third most valuable sector in the MSCI World index, representing 11.9% of that index’s capitalisation.

Banks

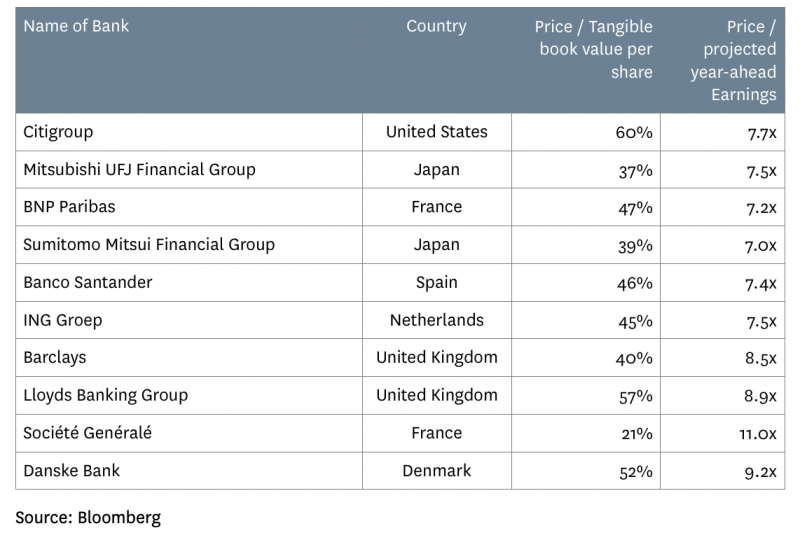

Banks in particular used to represent almost 12% of the MSCI World index but have now fallen to a weighting of less than 5%. While the decline in banks’ share of market capitalisation partly reflects a decline in their share of corporate earnings, it is also due in large part to a decline in relative valuation multiples. While valuation multiples for the rest of the share market have increased over the past decade, valuation multiples for financial sector companies (particularly banks) have declined. Around the world, we find many banks with strong market positions and robust financial strength trading at valuations of about half of tangible book value and/or single digit price earnings multiples. A few examples are shown in the table below:

Some examples of statistically cheap banks

On the face of it, price / earnings multiples of less than 10 imply that investors could expect long term returns from investing in banks of more than 10% per annum if the current level of earnings can be maintained and the banks make the most sensible use of their earnings (which implies paying earnings out as dividends if they can’t achieve good returns from retaining the earnings within their business).

Many of these banks are having to deal with specific issues such as historical regulatory breaches, but they are generally working to resolve these issues and move forward. Investors can buy credit protection for any of these banks for a cost of less than 0.6% per annum, which implies that fixed interest markets, at least, are taking a view that the downside risk for each of these banks is limited.

Why does the market value banks at such large discounts to asset backing and low multiples of earnings while other companies are being valued on much richer multiples? In theory, banks could deliver rich rewards to their shareholders simply by liquidating their assets and distributing the proceeds to shareholders. But assuming they don't do this, how should we think about the long term returns that investors could achieve from investing in banks?

The key reasons why investors might doubt whether banks will deliver sufficient long run returns to shareholders are their higher-than-average risk and their lower-than-average returns on invested capital:

- I say "higher-than-average risk" because banks will often fall slightly harder than the rest of the market during a large market decline. This should not be a surprise, as they are exposed to the broader economy through their lending activities, and their sensitivity to this exposure is amplified by financial leverage. The systematic risk of investing in banks was most apparent during the global financial crisis. However, they won't always underperform in a market downturn, as demonstrated by the fact that bank shares outperformed the broader global equity market during the "tech wreck" of the early 2000s. Looking forward, I would argue that it is prudent to assume that if the market declined by 20%, banks might typically fall by something in the range of 22% to 25%, and the extra risk implied by this assumption would suggest that investors should require returns from banks that are 1% to 1.5% higher than the returns they might demand from the typical listed equity.

- Poor returns on invested capital are a problem for investors in banks because banks will typically retain a portion of their profits within their business and only pay the remainder out as dividends. If a bank is earning a lower return on every dollar of equity than its shareholders would expect to achieve if they were investing that money themselves, then it makes sense to value each dollar of reinvested earnings at slightly less than 100 cents in the dollar.

There are a number of reasons why banks' returns on equity are currently much lower than the returns achieved by many other sectors. The most structural reason is the fact that most banks achieve most of their earnings from relatively homogenous services that are not strongly differentiated from each other. Banking customers know that key products like lending, transactional accounts, and credit cards work pretty much the same way regardless of which bank they use, and this limits the opportunities for banks to boost the margins that they earn on these services without losing market share. There are also a number of more recent factors that have adversely affected bank profits over the past few years, but which may not persist for ever. These include:

- the effect of lower interest rates (which mean that banks can no longer make good margins from investing both shareholders' equity and the funds they receive from transactional balances);

- regulatory changes that have forced banks to hold more capital, spend more money on compliance, and pay higher-than-wholesale rates to attract "sticky" retail deposits;

- the fact that economy-wide demand for credit has "only" been growing at about the same speed as the broader economy, slower than the double digit demand increases that boosted bank profitability before the GFC.

For banks that are concerned with looking after the interests of shareholders, one logical response to poor returns on capital would be to take measures such as increasing fees and margins or closing branches to offset the cost increases they have faced, accepting that these measures would lead to some loss of market share. In banking, losing market share in lending is not so bad for shareholders, as it automatically leads to a reduction in the amount of capital that a bank requires, thereby allowing greater dividends to shareholders.

Although no radical change in the behaviour of bank boards and management seems likely, I would expect that over the next decade or so, a likely consequence of banks continuing to earn low returns on equity and seeing their share prices continue to trade at significant discounts to net asset value will be that they will gradually place more emphasis on improving margins and increasing dividends, while reducing the emphasis on maintaining market share. This would likely lead to a general narrowing in the discounts to net asset value that much of the sector trades on.

But even without such a change, bank shares are now being valued at levels at which it is possible to see good long term returns whilst the banks themselves continue to do poorly. Consider a typical example of a bank achieving just a 6% return on equity and paying out 40% of profit as a dividend whilst its share price languishes at half of net asset backing. If such a bank maintains this steady state of 6% ROE and 40% dividend payout, its asset backing would increase at 3.6% per annum while shareholders receive a dividend yield of 4.8%. Assuming the share price remains at a 50% discount to asset backing, the total shareholder return of 8.4% per annum would be a roughly adequate return in the current environment of near-zero interest rates. If we assume even a very gradual improvement (say return on equity improving by 0.1% per annum while the share price discount to NAV narrows over the next 20 years to -30%), then it is very easy to see how an investment in this typical bank could potentially deliver double digit average returns to shareholders over the next two decades.

Insurers

In many ways, the investment characteristics of general insurers (known as property & casualty insurers in most parts of the world) are effectively "banks-lite". They face some of the same issues as banks, but in a less extreme manner. General insurers have historically earned a significant share of profits from the interest they earned by investing the money they receive as insurance premiums in the fixed interest market, and as such their returns have suffered in recent years due to the decline in interest rates.

To some extent, many insurers share the same problem as banks of being unable to really differentiate themselves from their competitors, but there are nonetheless many insurers that are able to achieve strong returns on capital because they've successfully differentiated their offering in the minds of customers, or because they operate in a specialist area of insurance with relatively few competitors.

Property and casualty insurers also tend to be less risky than banks, because even though they typically invest a large proportion of their investment portfolios in fixed interest securities that could lose value if there is economy-wide financial stress, they are not typically as leveraged as banks, and any credit losses are therefore likely to only represent a modest percentage of their capital base.

Reflecting these characteristics, shares in property and casualty insurers are generally priced on slightly higher multiples than banks, although these multiples are still considerably lower than the average valuation multiples seen in the rest of the equity market. In many cases, we believe that property & casualty insurers are (like banks) priced on sufficiently undemanding multiples to offer the prospect of attractive long term returns to shareholders even if we assume that returns that companies themselves achieve will continue to be uninspiring.

Life insurers are generally a riskier proposition than property and casualty insurers, as they often invest significant portions of their portfolios in equities, and investors are required to place a lot of trust in the assumptions made by the actuaries who value their liabilities. In some cases, these life insurance liabilities consist of multi-decade investment return promises made in times when interest rates were much higher, and the true cost of these obligations could be much higher if low interest rates persist. Life insurers often trade on even lower valuation multiples than banks but, given the uncertainty about the reliability of their balance sheet valuations and earnings, these lower multiples may well be justified.

Conclusion

Although they face some challenges, banks and insurers are currently priced on valuation multiples that offer the prospect of good long term returns, and they therefore ought to have a significant place in many diversified investment portfolios.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios that hold shares in Citigroup, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group, Lloyds Banking Group, and Danske Bank.

When I bowed to the consensus view that banks were deadbeats in the mid-1980s, I inadvertently missed out on investing in ANZ shares prior to a 20-year period of compound returns of more than 20% per annum