The Future May Not Be As Rosy As Equity Investors Assume

NBR Articles, published 9 March 2021

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall, originally appeared in the NBR on 9 March 2021.

US-based companies represent over 55% of the investible capitalisation of the global equity market. Accordingly, the returns that equity investors should expect from investment in global equities will depend critically on future returns from the US equity market.

While the volatility of equity markets always means there is a wide range of possibilities as to what sort of returns an equity market may deliver over shorter periods of up to 5 years, the returns over longer periods inevitably have to be tied mainly to the prospects of the underlying companies, and the price you pay to invest in them. Long term returns will be derived from two sources – (1) the net cashflows that listed companies can distribute to shareholders; and (2) growth in the market value of listed companies, which over the long term must be derived primarily from growth in corporate earnings.

In this article, I'm going to discuss what long term returns investors may reasonably expect from US equities over the next quarter of a century.

Corporate Earnings Growth is key for long-run Equity Returns

From today's starting point, the most important determinant on long-run equity returns will be growth in corporate earnings. Historically, over the long term, the aggregate profitability of all companies has tended to grow roughly in line with the economy, as we should logically expect, because the only way that corporate profits could grow faster than the economy over long time periods would be by squeezing out the share of income going to wages and salaries, but corporate profits could not keep on increasing for very long if wage and salary earners had less and less money to spend on the products and services that corporations produce.

Long term Corporate Earnings growth will be closely linked to GDP growth

The inevitability of total corporate earnings growing broadly in line with the economy means that the aggregate earnings of any cohort of existing companies will tend to lag behind the growth in the economy, as the cohort of existing companies will progressively give up a share of the profit pie to newer companies. If you had invested in the US sharemarket 40 years ago, you would not have bought a single share in any of the six largest companies of today (by market capitalisation), because none of those six companies were listed in 1981 (Apple & Microsoft were both founded in the 1970s, but did not list until later in the 1980s). So the only way that someone investing in the US sharemarket 40 years ago could now own a slice of every company that is listed today would have been by selling shares out of their existing portfolio in order to buy into every new company that lists on the sharemarket. By progressively selling down a portion of the shares that they already held, this investor’s portfolio would have experienced lower look-through earnings growth than the aggregate growth of the US economy. This pattern will undoubtedly continue into the future - some of the largest companies in 2061 will probably be companies that do not even exist today.

As a general observation, when you sell shares in long-established companies to fund your purchases of shares in newer recently-listed companies, you often have to pay a higher earnings multiple to buy into the newer “up and coming” companies. People investing in equities now should anticipate that many new companies will be listed over the years ahead, and that the process of selling down the portfolio’s holdings of existing companies to buy into the newer companies will likely stretch the overall valuation multiple of their portfolios.

While I previously made the point that aggregate corporate earnings grow broadly in line with the economy over the long term, it is important to acknowledge that corporate earnings’ share of GDP can cycle up and down from one decade to the next, and the corporate earnings share of GDP is currently close to its historic peak as a proportion of GDP. This means that if anything, the balance of risks is towards corporate earnings growing slightly slower than the broader economy over the next quarter-century. The likelihood of profits falling as a percentage of GDP at some stage over the next 25 years is increased when you consider that governments are currently spending a lot more cash than they’re receiving, with the flipside being that other sectors of the economy (including corporates) are receiving much more cash than they’re spending. When government fiscal deficits normalise, we should expect this to put downward pressure on corporate profits.

But back to the key issue: what are the prospects for US GDP growth over the next quarter-century?

Based on the experience of the past 100 years, economists have got used to projecting real GDP growth rates of about 2.5% per annum, which equates to nominal growth of about 4.5% to 5.0% when we take account of inflation. However (as discussed below), I think there is a real danger that future economic growth could be much lower than that.

Long-term historical norm was for very slow GDP growth

As revealed in Gregory Clark’s book “A Farewell to Alms” (2007), the longer term norm throughout human history had been for real GDP growth rates of about 0.1% per annum and zero per-capita GDP growth. For most of history, from ancient Babylonia 3500 years ago until the early stages of the industrial revolution 250 years ago, records show that a large proportion of the population of each society subsisted on incomes that were barely sufficient to cover basic food and shelter.

Although technological innovations meant that these historical economies improved farming productivity over time and therefore grew the aggregate output of their economies, growth was never fast enough to stay ahead of population growth. Rather, the historical pattern was for populations to expand to consume whatever food supply was available, ultimately breeding themselves back into a position of malnutrition. When 18th century European explorers marvelled at the tall physiques of the Māori, they were not observing some particularly tall genetics, but rather encountering one of the few agricultural societies in the world that had not yet bred itself into malnutrition (at that time, malnutrition meant that the average European was a lot shorter than they are today).

Long-term outlook for GDP Growth?

So, to summarise, the norm had been for virtually no GDP growth until the late 18th century, and then something changed which that meant that for the first time in history economies could out-pace their populations for decade after decade.

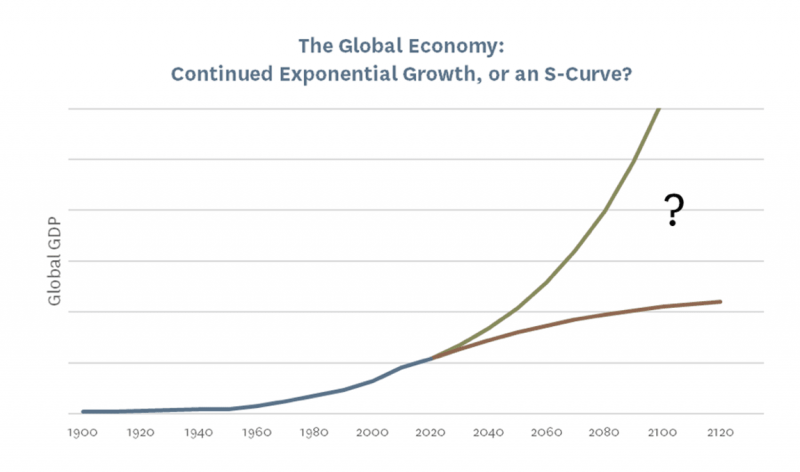

Global growth rates gradually climbed above 1% during the 19th century, and the world economy has now been growing at an average rate of about 3% per annum since the start of the 20th century (although in recent decades growth rates have slowed to about 2% per annum for already-developed economies). Are 2%+ growth rates the new normal that will persist indefinitely into the future? Or are we in the middle of a big S-curve that will end with GDP growth slowing down to something much closer to zero?

To answer this, it pays to think about what had fundamentally changed when the industrial revolution began in Britain in the late 18th century.

There are a number of factors that arguably contributed to the start of the industrial revolution (and hence the era of meaningful GDP growth). These factors included relatively high literacy/education (at about 50% literacy, Britain possibly had the most literate population in the world at the time); Britain’s trade with its colonial empire; and strong property rights (the British legal system meant that business owners didn’t have to worry about aristocrats just helping themselves to business assets and profits, and Britain had a patent system that incentivised innovators by allowing them to profit from their inventiveness).

But another critical catalyst for the start of the industrial revolution was the first widespread use of fossil fuels. In 1720 virtually all iron and steel was produced with wood charcoal, and steam engines were little more than toys. One hundred years later in 1820, everything had changed: factories were being powered by (coal-fired) steam engines; British iron production had increased 6-fold due to a switch from wood charcoal to coking coal; railways were being built; and gas lighting was spreading throughout Britain. Since then, further global GDP growth has been driven by the invention and widespread use of oil drilling and refining, internal combustion engines, jet engines, and fossil fuel powered electricity generation. During the 20th and 21st centuries, economic activity and fossil fuel consumption have been closely linked: global GDP has grown by 3.1% per annum between 1900 and 2019, whilst fossil fuel consumption grew by 2.7% per annum over the same time period.

Now that the world is having to decarbonise, where does that leave the outlook for GDP growth? Fossil fuels are not only used to power most of the world’s vehicles and generate most of the world’s electricity, but also to produce many of the materials that are used in pretty much every industrial process. We have a global economy that increasingly relies on electricity, and most of the electricity in the world is produced in generation plant that is both powered by fossil fuels and constructed with materials made and transported using fossil fuels.

Future GDP growth depends on strong growth in Renewable Energy

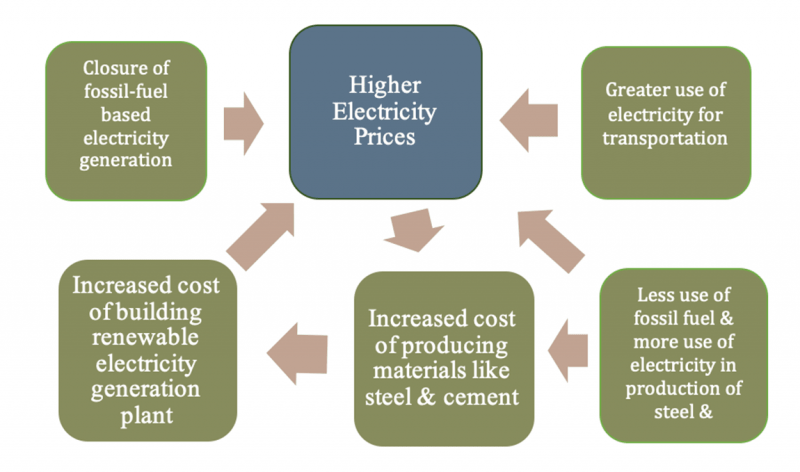

There will be a strong need for the world to build and maintain a lot of renewable-based electricity generation plant as the world continues to move towards: (1) powering more vehicles with electricity (hence increasing the demand for electricity); (2) reducing the direct use of fossil fuels in the production of materials such as steel (also increasing the demand for electricity); and (3) closing down fossil-fuel-powered electricity generation. Unless we see some revolutionary new technologies such as the development of economically viable nuclear fusion or major improvements in the energy efficiency of solar power, it seems likely that global prices for electricity would need to rise significantly to encourage the level of investment required. Renewable generation opportunities typically present themselves on a rising cost curve, with higher and higher prices required to justify further investment once the most viable projects have already been built.

The upward pressure on global electricity prices will likely be compounded by the fact that many forms of electricity generation make heavy use of materials such as steel, copper, and cement, all of which are currently produced using fossil fuels. These materials will likely become more expensive if producers switch to using electricity to produce these materials at the same time that electricity prices are rising.

How would higher electricity prices affect economic activity? This is not an easy question to answer. A supply-side shock, when a shortage of supply pushes up the price of an input used across multiple sectors, should in theory be negative for GDP growth.

However, the best historical example of a supply shocks were the oil crises of 1973 and 1979, and although the spikes in oil prices that occurred in these years did cause their share of economic problems (including recessions in most developed economies), the global economy continued to grow at a healthy rate after it had adjusted to higher oil prices. Hence, an optimistic view on the transition to renewable power generation would be that it may only be a temporary impediment on growth. Maybe the economic activity associated with building renewable generation plant will largely offset the adverse impact on economic activity from higher electricity prices.

However, I'd be cautious about dismissing the magnitude of this problem and the impact it could have on economic growth, and can easily see scenarios where turning off fossil fuel plant may mean that major economies might not be producing much more electricity in 30 years' time than they are today. After taking account of the increases in electricity demand that we might see from electric vehicles, changes in how materials like steel are produced, and the seemingly inevitable growth in demand growth from data centres, it is easy to envisage that higher electricity prices could "crowd out" more traditional sources of electricity demand, which could contribute to a prolonged period of moribund growth.

At a more abstract level, it is not at all clear that humans have completely escaped the basic rules that govern all populations in nature. And the lesson from nature is that while populations will sometime go through a period of what looks like exponential growth, it ultimately always proves to be an S-curve (or worse, a boom-and-bust). Humans' share of the world's biomass and energy capture is unprecedented in a billion years of pre-history, and it is not at all clear that the global economy can continue to expand from our existing energy footprint.

For these reasons, I think it is prudent to assume that the global economy may only grow at about 2% per annum over the next few decades. Assuming that developing economies continue to catch up with more developed economies like the United States, the US economy may only grow at about 1.5% per annum. If aggregate US corporate profits also grow at 1.5% per annum (in real terms), we should probably assume that the profitability of the existing cohort of listed companies grows at about 1.0% per annum, with the balance of the growth captured by new up-and-coming companies that will list on the sharemarket in future years.

Taking account of inflation, this implies that the profitability of currently-listed US companies will grow at about 3% to 3.5% per annum in nominal terms.

Of course, the other element of the return to equity investors is the cash that companies can distribute to shareholders, either by way of dividend or share buybacks. Against these distributions, we need to net off the cash that companies effectively take back from shareholders by issuing new equity. Based on the fact that the US equity market currently trades on a price/earnings multiple of over 30 times (i.e. an earnings yield of 3.3%) and the likelihood that US companies will need to retain about a third of their earnings to reinvest in their businesses, it seems reasonable to expect that US companies will in aggregate provide cash distributions to shareholders of about 2.2% per annum.

Adding these two components together, and this exercise gives us a projected long run return from US equities of about 5.5% per annum (in US dollar terms). This is higher than the 2.3% return that investors could achieve by investing in 30 year US government bonds, but the implied risk premium of 3.2% per annum is not particularly attractive by historical standards. This projection is arguably a little on the bullish side, as it ignores the potential return drag (discussed earlier) that would occur if (in order to maintain a portfolio that was representative of the entire market) we bought into newly listed companies at higher average earnings multiples than our existing holdings.

Over a time period as long as 25 years, this projected return is not particularly sensitive to the assumptions we make about how the sharemarket will be priced in 25 years time. If the price/earnings multiple of the US share market rises to 40 times by 2046, we could project an internal rate of return (IRR) of 6.4% from an investment in US equities, but if it were to fall back to 20 times our projected IRR would fall to 4.2%.

All these potential returns are expressed in US dollars. The forward foreign exchange market builds in an implicit expectation that the NZ dollar will decline against the US dollar over time, which would slightly boost returns to investors measuring their returns in NZ dollar terms.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios that include significant investments in US equities, but are currently underweighted to the United States relative to its share of global market capitalisation.

There will be a strong need for the world to build and maintain a lot of renewable-based electricity generation plant… it seems likely that global prices for electricity will need to rise significantly to encourage the level of investment required..