The Trend Can Be A Fickle Friend

NBR Articles, published 22 June 2021

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall, originally appeared in the NBR on 22 June 2021.

The simplest form of investment decision-making is to form a view based on whether a stock has been going up or down. Arguably it is also the common form of investment decision making, as most investors are influenced by share price movements (whether they’re aware of it or not).

Some investors seem to have a strong preference for buying stocks that have been strong in recent months, while others seem to have a strong preference for buying stocks that are trading lower than they have in the past, figuring that a lower share increases their chances of getting a bargain.

From my own observations, it often seems that the determinant of whether a particular investor prefers to "go with the trend" or "look for bargains" is almost hard-wired into their DNA. Many people have a strong bias toward one of these two approaches. Of course, people also try to learn from experience and (sometimes) from empirical studies. Unfortunately, confirmation bias means that they often pay most attention to the experiences and studies which support their original bias.

So who is right? In investing, is it generally more advisable to go with the trend, or to fight it?

On balance, history suggests that going with the trend has worked better than trying to fight it in equity markets. Various studies have shown that a strategy of investing in stocks that are selected for having produced better than market returns over the previous 6 to 12 months would have outperformed the market over time. Further, empirical studies show that "long/short strategies" where an investor would have invested in the stocks with the best returns (over the past 6 to 12 months) whilst shorting the stocks with the worst returns (also measured over the 6 to 12 several months) would have produced positive returns on average over time, which would have had the desirable feature of being negatively correlated with overall share market returns.

No magic formulas in investing

However, there is no such thing as a magic formula for consistently generating excess returns in investing, and momentum-based stock selection strategies are no exception. History shows that returns from momentum-based stock selection are very volatile, and can be subject to significant drawdowns, such as occurred between February and August of 2009, when indices of returns from momentum-based strategies indicate that they destroyed more value than they had added in the previous 10 years. In fact, Citigroup's index of returns from a long/short momentum strategy applied to developed equity markets is currently at a slightly lower level than it was in February 2009, indicating that despite generally healthy returns from momentum investing over the past decade, it has not yet recovered from the 2009 wipe-out.

Further, the historical record only really shows evidence that momentum-based stock selection adds value for large liquid stocks if the "look back" period is between 6 and 12 months. If you look back over much shorter time periods – between a day and a week – there is evidence that trading against the market direction has historically worked far better. In fact, if you don’t allow for transaction costs, the back-tested returns from short term "price reversal" strategies often have a far higher degree of statistical significance than the historical returns from momentum strategies based on longer look-back periods. However, you would need to have transacted very well (and paid low commissions) to have exploited these returns, as strategies designed purely to exploit short term price reversal will typically involve average holding periods of a week or less.

Purely momentum-based stock selection strategies based on look back periods of 6 months to a year would also involve far higher trading activity than most other forms of quantitative stock selection, such as quantitative screens based on measures of quality, value, low risk, or growth.

In my view, the high level of trading activity for investment strategies based purely on price momentum or price reversal makes it a poor idea to run portfolios purely based on these strategies, a view that is strengthened by the potential underperformance of momentum investing in environments similar to 2009. However, iShares run a couple of momentum-based ETFs that are investing a total of over US$17 billion of investors' funds, and to date these ETFs have outperformed their investment universes over the few years since they were launched.

High turnover of momentum and price reversal strategies makes them potentially vulnerable to crowding if many investors are selecting stocks on the same criteria. For example, if several "momentum investors" are building portfolios consisting of stocks with the best one year return, then they might all try to sell out of the same stock exactly 365 days after its price spiked, with their collective behaviour probably destroying their average exit price. And when a share price spikes up for some non-fundamental reason (e.g. stock-pumping on Reddit's Wall Street Bets forum), momentum investors will add to the volatility, by all piling into the stock at the same time. In fact, the amplification of short-term share price movements by momentum-based investors could be a factor contributing to opportunity to profit from short-term price reversal.

Given that momentum investing and short term price reversal have both added value over the long term, it is worth thinking about why they have worked, and incorporating any insight this may give us into our investment approach. While I previously argued against investment strategies based purely on price momentum or price reversal, I believe that it is useful to incorporate insights about why these strategies have historically added value into an investment approach that is anchored in fundamental analysis.

In particular, a better understanding of why price momentum has historically outperformed can be a good complement to a value-based investing style, where there is a real risk of continuing to add to a holding as its share price falls further below an out-dated view of the company's true worth. And an understanding of short term price-reversal can improve your trading performance when you are adding to or selling down portfolio holdings.

Of course, the Efficient Market Hypothesis predicts that a momentum (or price reversal) based strategy should not add value, as market prices should in theory incorporate all available information about a company at any point in time. In theory, this would include any trends in the company's performance, such that any new information is just as likely to be a positive surprise as a negative surprise.

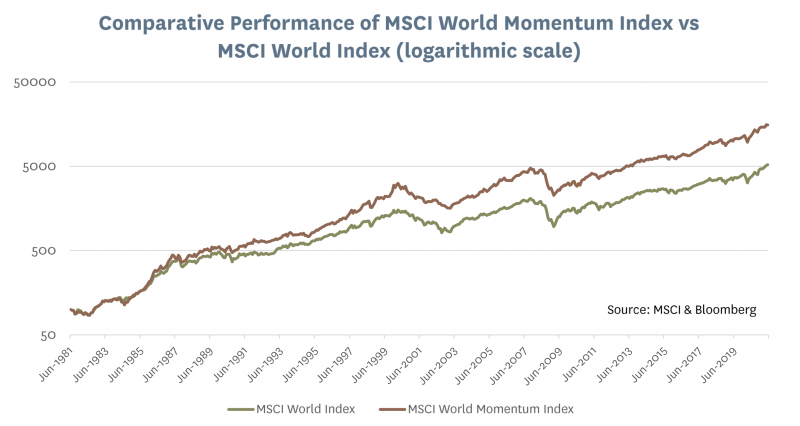

Diehard believers in the Efficient Market Hypothesis often start from this perspective, so when the evidence of historical outperformance of momentum investing survives all statistical tests of significance, they write academic papers arguing that the incremental return is just compensation for some subtle form of risk that other authors hadn't identified. However, these papers often read a bit like biblical scholars finding evidence of Noah's flood in fossils of dinosaurs, and a casual glance at the graph above should satisfy most people that over longer time periods momentum-based stock portfolios don't seem to be markedly riskier that the broader equity market.

To my thinking, a better explanation of the long-term outperformance of momentum investing is that investors are often anchored to the views that they have previously formed about the outlook for companies. This anchoring means that investors have a tendency to initially under-appreciate the significance of new emerging trends or risks that could ultimately result in some companies being worth several times as much as the market currently values them at, or conversely could result in the value of a company collapsing to a fraction of its current valuation. In other words, investors have (on average) tended to under-react to new fundamental information about companies.

Another possible explanation for the performance of momentum is that a share price may be drifting in one direction because well-informed people with intimate knowledge of a company or its products may see an emerging competitive threat or growth opportunity before it has been reported in mainstream media. If the collective investment decisions of a number of well-informed people affects a share price, momentum investor who follow its trend may get to benefit from some unknown development before it has been widely reported.

While some people like to think that the good performance of short-term reversion is about taking advantage of investor "over-reaction", I prefer to think of it as taking advantage of trading "noise", where a share price is being buffeted around for no reason other than an imbalance of buy and sell orders that were not initiated due to some new fundamental information about the company. In particular, I notice that trading against short-term market direction is most reliably profitable when the share price movement is caused by a technical factor such as a stock moving in or out of an index, or a sell-down by a major shareholder, and it is most dangerous when the share price is reacting to new information about a company (for example an earnings release). While markets sometime over-react to new information, in many environments there is a greater tendency to initially under-react.

Whether we're looking at a share price movement from a short-term price-reversal perspective or a longer term "momentum" perspective, the key question is essentially whether the share price has been moving too much or too little relative to potential for the value of the company to change over time. It is therefore important to have a good understanding of the range of future possibilities for a company before jumping to conclusions as to whether a share price is likely to be over- or under- reacting to new information.

For some companies, we can be relatively certain that their value in several years' time is likely to be of a similar order of magnitude to their value today. For example, a regulated electricity distribution network with modest debt is unlikely to disappear but also unlikely to double in value over a short space of time. Buying or selling such companies on the basis of price momentum rarely adds value, as their share prices are unlikely to keep moving in the same direction.

But for other companies, the range of future possibilities may far wider. For example, emerging "challenger" companies that haven't yet hit profitability sometimes keep growing until they're the new market leader, but sometimes they're effectively shut out of business when an incumbent effectively addresses their threat. And heavily indebted companies that have seen their share prices smashed on the back of disappointing results sometimes go all the way to zero, but sometimes they recover and return to their previous valuation. For these sorts of companies, it can be dangerous to bet on price reversal, as the share price could keep going in the same direction.

The market environment can also be an important determinant of whether price momentum or price reversal will work better. In stable environments, when share prices aren't changing much from day to day, there is a greater probability that any drift that you see in a share price is an under-reaction to some underlying trend. In these environments, the trend is more likely to be your friend for many companies. But when markets are extremely volatile (such as during the GFC when many share prices seemed to rise or fall more than 5% virtually every day), the size of short-term price movements can be way out of scale with the range of possible longer-term valuations for a company. In these volatile environments, buying low and selling high can add a lot of value to a portfolio.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited

…these papers often read a bit like biblical scholars finding evidence of Noah's flood in fossils of dinosaurs…