Understanding Equity Market “Style Factors”

NBR Articles, published 22 October 2024

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall,

originally appeared in the NBR on 22 October 2024.

The maxim that “birds of a feather flock together” often seems to apply as strongly to the share market as it does to ornithology. “Stocks of a feather” flock together as well.

Stocks of a Feather flock together in funds

You will often see “stocks of a feather” sitting together in the portfolio of an investor or fund manager who has a strong leaning to a particular type of investment. For example, a fund manager who leans towards growth may hold a lot of “growth stocks” in their fund, while an investor who leans towards value may have a lot of “value stocks” in their fund.

Most active fund managers have at least some tendency to lean towards certain types of stocks. This will often be considered a key aspect of their investment style or approach. “Growth managers” tend to lean towards “growth stocks”, “value managers” tend to lean towards “value stocks”, and so on.

Stocks of a Feather flock together in performance

“Stocks of a feather” tend to flock together not just in terms of which funds and portfolios they sit in, but also in terms of how they perform.

For example, in any given day or month, you may see that most of the best performing stocks are “momentum stocks” (which can be roughly defined as stocks that have produced the best returns over the prior year) while the worst performing stocks are all “poor momentum stocks”. On other days it will be the other way around, with the “poor momentum stocks” all rallying while the “momentum stocks” all decline. On many other days, the market will bifurcate on the basis of some other factor, like “value” or “growth” or “risk”.

In short, stocks exhibiting similar characteristics often move up or down together, which can add to variability of investment performance for investors or fund managers with a strong preference for that particular characteristic.

Amongst the quantitative investing professionals, these common-followed investment characteristics that are often associated with similar stocks rallying or declining together are known as “style factors” or simply “factors”.

Measuring the performance of factors

A common way to measure the performance of a particular style factor is by looking at the difference in returns between those companies in the market that are most aligned to a particular investment style and those companies that are least aligned to that investment style.

For example, if we want to evaluate how the equity market is treating value investors, we can do this by comparing the share market performance of the cheapest companies in the market (based on simple valuation metrics) to the share market performance of the most expensive companies in the market. Rather than choosing just a single valuation metric (which could lead to anomalous results) it generally works better to measure companies on several different valuation metrics (price/earnings multiple, price/book, enterprise value/EBIT, etc) and to use a composite “valuation score” to sort companies into buckets from “cheapest” to “most expensive”.

We can then look at the returns you would have got over time if you had regularly sorted companies into “cheap”, “expensive”, and “middling” buckets based on this approach and invested in the cheap companies while taking short positions in the expensive companies.

While it would take a lot of work to build our own measures of how different style factors have performed, we are fortunate that brokers and index providers are doing this work for us, and we can use their hard efforts to get insights about how the market is treating different style factors.

I like to use a set of factor indices published by Citigroup’s quantitative team to keep track of how different factors are performing. Citigroup’s factor indices measure the performance of seven style factors: Value; Growth; Price Momentum; Quality; Low-Risk; Earnings Revisions; and Size.

The variant of the Citigroup factor indices that I like to use tracks the performance that you would have got if you had simultaneously taken long positions in the 20% of stocks that scored most highly for a given factor while taking short positions in the 20% of stocks that scored most poorly on the same factor.

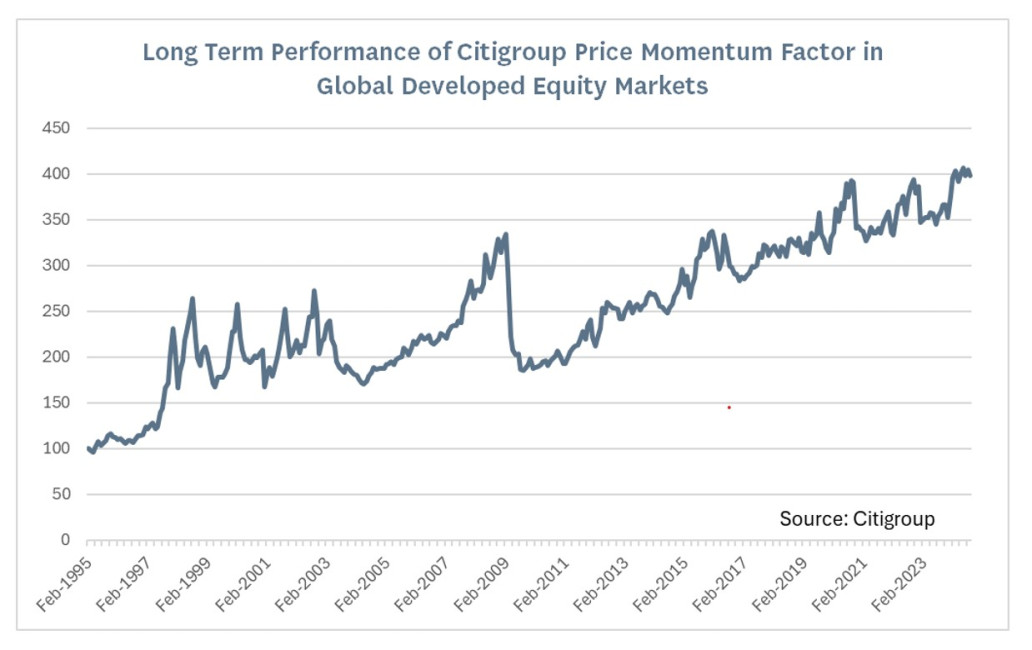

As an example of this, the graph below shows the long-term performance of Citigroup’s Price Momentum index for global developed market equities. This index tracks the relative outperformance of the 20% of stocks selected for having the strongest trailing share price performance compared to the performance of the 20% of stocks selected for having the weakest trailing share price performance.

As you can see from this graph, this relatively naïve strategy of essentially buying recent winners and selling recent losers has worked well over time, although the results have been volatile. In particular, the price momentum factor performed particularly poorly when global equity markets bounced back from the global financial crisis in 2009.

How have the different factors performed over time?

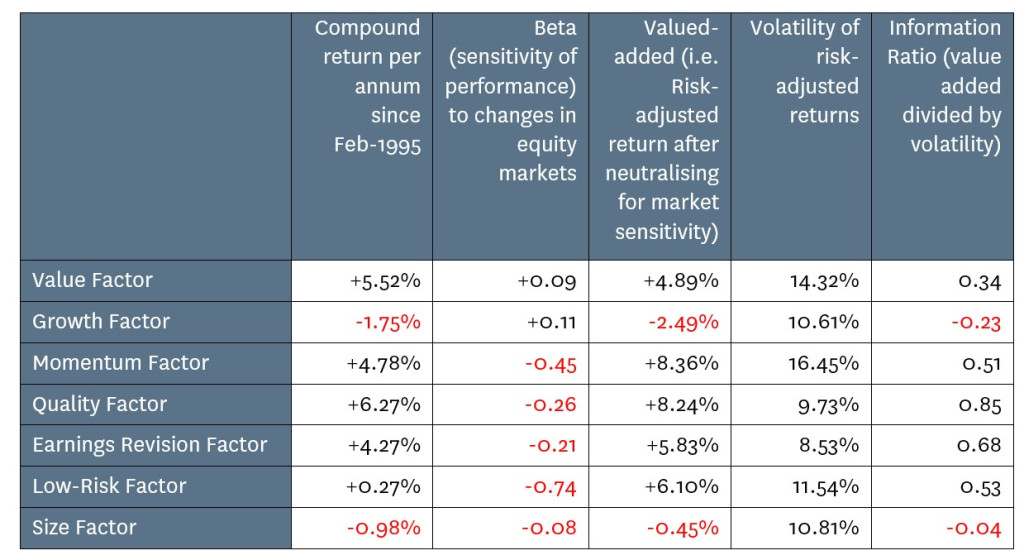

In the table below, I present some long-term performance statistics and characteristics for style factors in global developed world equities, using each of the 7 factors which Citigroup measure with their factor indices.

Each of these factors represents the returns from the 20% of stocks that scored most highly for a particular investment style minus the return on the 20% of stocks that scored most poorly for the same investment style.

The first numeric column shows the simple calculation of the return that you would have got from following the simple long/short strategy implied by each factor.

In the second column, I show how sensitive each market factor is to changes in the overall level of the equity market (for this table I used the sensitivity (beta) to global equity markets measured in local currency terms). This is important, as the dominant source of risk in any equity portfolio will be movements in the overall level of the share market. As this table shows, different investment styles can either add to or reduce your portfolio’s overall sensitivity to the overall share market.

Importantly, as the second column shows, the most commonly-followed strategies of “growth investing” (investing in the companies that are growing the fastest) and “value investing” (investing in the cheapest companies) tend to behave a bit like camouflaged leverage – they typically make your portfolio slightly more sensitive to declines in the overall share market.

By contrast, many other investment styles are more likely to reduce your share portfolio’s sensitivity to market declines. These risk-reducing investment styles include: momentum (buying recent share market winners and selling recent share market losers); quality (favouring stocks that score well on a number of metrics that attempt to measure companies on various “quality” criteria such as profitability, earnings certainty, and balance sheet efficiency); earnings revisions (favouring stocks where expectations for future earnings/revenue/cashflow are improving and avoiding companies where expectations are declining); and low-risk (favouring companies with low debt, stable earnings, less-volatile share prices, and low sensitivity to the share market).

In the third column I show the long-term performance of each factor after adjusting the returns to exclude the element of each factor’s performance that can be statistically explained in terms of the factor’s sensitivity to movements in the overall level of the market. This column shows that 5 investment styles have tended to add significant value over time (since 1995). These have been: value investing; momentum investing; quality investing; investing based on earning momentum; and low-risk investing.

“Growth” hasn’t worked over the past 30 years?

Interestingly, the seemingly most-popular investment style – growth investing – is the one investment style which empirically seems to have detracted value over time, based on the Citigroup factor index. Perhaps the ease with which marketers can sell high-fee “growth” equity funds to retail investors means that there is always a surplus of capital competing for growth stocks, which may explain the poor long-term returns from the “growth” factor.

Another potential explanation for the poor performance of the “growth factor” could be that Citigroup’s quantitative methods don’t do as good a job at capturing the essence of growth investing as they do with other investing styles. This is probably at least partly true, but is at best only a partial explanation, as the majority of growth-orientated fund managers fail to outperform quantitatively-based “growth” benchmarks. Some other analytical approaches will attribute better returns to growth than implied by Citigroup’s growth factors index. In particular, some analyses include aspects of what Citigroup would define as quality investing (e.g. high return on equity) in their definition of “growth investing”.

This table also showed that selecting stocks based on their market capitalisation has not made much difference to performance over the past 30 years. Overall, a tilt towards “size” (i.e. favouring large capitalisation companies) has modestly detracted from risk-adjusted investment returns over that period.

In the penultimate column, I show the volatility of the market-adjusted returns from each style factor. In a sense, the more volatile a style factor is, the more evidence there is that “stocks of a feather” are flocking together, and the investment criteria is truly behaving as a true “market factor”.

As investment professionals, we love to identify investment characteristics that tend to predict out-performance but are not associated with stocks moving up and down together. Identifying such characteristics is great, because the law of large numbers means that if you invest in enough stocks with these favourable investment characteristics, you might expect this to lead to consistent outperformance over time. What often happens, however, is that when other investors become aware of the predictive power of a particular investment characteristic, it suddenly starts to behave like a factor, in that all the stocks that have that characteristic seem to be bought or sold at the same time, and this “flocking behaviour” means that the incremental performance that you might expect from your favoured investment characteristic becomes more volatile over time.

This pattern played out in the 1990s with many “quality” characteristics, which had previously only been identified by a few investors who enjoyed investment success from selecting stocks based on criteria that no-one else was following. As these quality characteristics became better known, “quality stocks” began to flock together, and the returns from the “quality factor” therefore became more volatile.

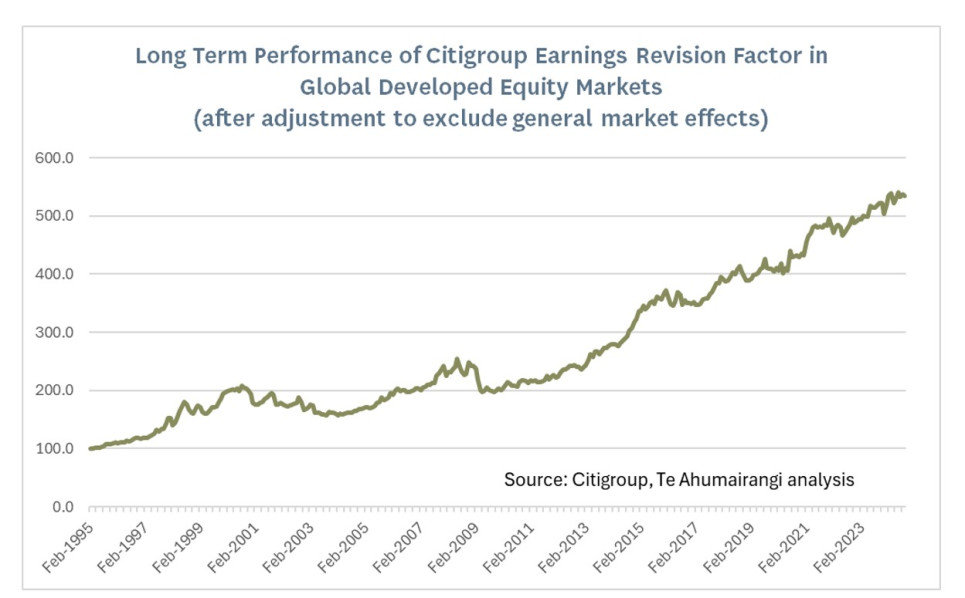

The volatility column indicates that Momentum is the whippiest factor, and that of all the factors shown in the table, Earnings Revisions had the lowest volatility, indicating that it behaves least like a factor. As the graph below shows, the Earnings Revisions factor has delivered reasonably consistent performance over time without wild swings in performance from one year to the next:

In the final column on the table, I calculate an information ratio which divides the long-term value added by each factor by the volatility of that factor’s performance. This column shows that while Momentum has delivered the best “raw” performance over time, the extreme volatility of returns from momentum investing means that it has ranked behind Quality, Earnings Revisions, and Low-Risk on a “bang-for-buck” basis.

Does past style performance predict future style performance?

Statistical analysis of style factor returns shows that they have a strong tendency to trend in the short-term. Specifically, factors that have added value over the past month are likely to add value in the following month, and vice-versa for factors that have detracted value.

However, this trending does not persist when you look over longer periods of time (e.g. 1 to 5 years). If anything, factors that have done relatively well over the past two to three years are more likely to do relatively poorly over the following two to three years. In my view, this reflects the tendency of many investors to “crowd” into whatever has been working in investment markets - up until the point at which the weight of their money ensures that it can no longer work.

Although factor returns do not trend over periods of a few years, I believe that there is valuable insight to be gained from looking at which factors have added value over the past 30 years, and working on the presumption that approaches that have worked well over this extended period of time are also likely to work well in the future.

The fact that certain quantitative investment criteria have helped to pick performance over such a long period of time probably indicates that these criteria take advantage of some innate psychological biases or blind spots of many investors. No amount of technology will prevent these psychological biases and blind spots from bubbling up in the future.

No single quantitative criterion can work in every single year, because investors become aware when an investment characteristic has been a good predictor of performance, and they chase that characteristic until the market prices it more efficiently, such that it ceases to work for a while. But these things move in cycles, and investors eventually drift away from investment approaches that have stopped working. In my view 29 ½ years of history covers quite a few cycles in investment behaviour, and therefore provides a reasonably good indicator of what will likely work in the future.

[Value, Quality, Earnings Revisions, Low-Risk] > Growth

To re-iterate the conclusion from the final column of the table, it seems likely that you will get superior investment results if you consistently select stocks based on Value, Quality, Rarnings Revisions, Momentum, and/or Low Risk. However, there is no evidence that selecting stocks based on growth criteria has worked over the long-term. Retail investors who choose to invest in growth-orientated funds because they like the idea of growth investing are taking a blind leap of faith that has no long-term empirical support.

Is Smart Beta Smart?

One way that investors can choose to invest in particular investment styles is through “Smart Beta” ETFs which provide diversified exposure to stocks selected for their fit to a particular investment style, such as Value, Growth, or Low Risk. The fees on these ETFs will typically be higher than for purely passive ETFs, but lower than the fees charged by most active managers.

However, I am not a fan of smart-beta investing styles, which build portfolios based on a single quantitative factor. I have two key concerns about single-factor investing.

My first concern with single-factor investing is that when you only look at one thing, you will often miss seeing other aspects that tell you that this is a stock to avoid. If you invest in all the most attractive stocks ranked on a criteria such as “quality”, “growth”, low-risk”, or “momentum” you are by definition paying no attention to price, and no company is so great that you should buy its shares regardless of price. On the other hand, if you invest based entirely on “value” criteria, you are only paying attention to price, and not taking account of things such as the quality, growth trends, and risk characteristics of the company you’re investing in. Investing according to a pure value strategy could potentially lead to you owning shares in a lot of cheap-but-failing businesses.

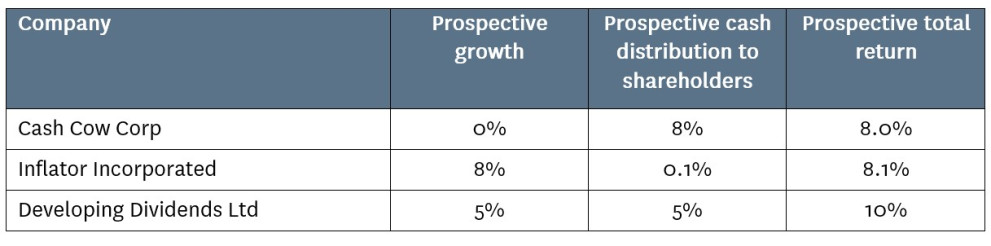

As an example of how investing on the basis of a single “smart beta” criteria can lead you astray, consider an investment universe that consists of the following three companies:

If you put all your money in a “Smart-Beta” Value ETF, you would probably end up investing exclusively in Cash Cow Corp, which would deliver you a return of 8% per annum. If you invested entirely in a “Smart-Beta” Growth ETF, you would probably end up investing exclusively in Inflator Inc, which would deliver you a return of 8.1% per annum. And if you split your money between the value ETF and the growth ETF, you’d have shares in both Cash Cow Corp and Inflator Incorporated, but you’d be missing out on the best stock of all – Developing Dividends Ltd (which would score well using a multi-factor quantitative approach). When you look at examples like this, it should be clear that “Smart Beta” is potentially very stupid.

My second issue with smart beta products is that they tend to be “long only”, investing only in stocks that fall in (say) the top quartile for a particular investment characteristic. But when I look at many studies on the long-term performance of stocks selected by different quantitative criteria, it is often apparent that quantitative investing works best by telling you what to avoid rather than what to own. For example, when you compare the performance of stocks allocated into different buckets based on criteria such as valuation, quality, risk, or earnings revisions, you often see that the “best stocks” have delivered roughly the same returns as the “second best stocks” and even the “third best stocks”, but that the worst 20% or so of stocks deliver much worse returns than the rest of the market.

This tells me that the best way to apply quantitative criteria to investing is often to take account of several criteria, and avoid any investment that scores particularly poorly on any one of these criteria. Long-only “Smart beta” products don’t do this. They rely on the fiction that quantitative factors work equally well from the long side, and select stocks that score well based on a single quantitative factor.

Investment Style can explain a lot about fund performance

If you look at which funds achieve the best or worst investment returns in any one year, you will often observe that most of them have a very similar investment approach. In 2022, the top performing global equity funds were mainly managed by value, quality, or low-risk orientated fund managers. In 2023 the top-performers were mainly growth managers. And in the first 9 months of 2024, many of the top-performing global equity managers seem to have more of a momentum-based approach.

The tendency for fund performance to be dominated by investment style raises some obvious questions:

- Which fund managers have only produced good performance because they happen to have followed the investment style that happens to have performed best over whichever period you are looking at?

- Which fund managers are truly adding value over and above the performance implied by their investment style?

There is ample evidence that the performance of a particular investment style over a period of 1 or 2 years tells you virtually nothing about how that particular investment style will perform over the next 1 to 2 years. Associated with this, there is also very little correlation between how fund managers perform from one year to the next.

However, I believe that when you separate out the aspects of a fund manager’s investment performance that are simply a consequence of their investment style, the remaining out- (or under-) performance provides useful insight about whether they’re truly adding value. Importantly, this residual relative performance, which I like to think of as the “underlying outperformance” is often markedly less volatile than a simple measure of relative performance and seems to have a reasonable tendency to persist over time.

How do you work out how much of a fund manager’s performance is due to investment style?

An obvious approach to evaluating fund performance is to compare each fund to other funds with a similar investment style. Some surveys of fund performance do exactly this, by grouping funds into a handful of categories such as “value”, “growth”, and “core”.

However, this can be a crude approach, because investment style is best explained on more than one or two dimensions, and there can be a lot of variation in how strongly different fund managers lean towards particular investment styles. For example, “hard core” growth managers may always prefer the fastest growing company regardless of the price they are paying for it, whereas other “growth-leaning” fund managers may pay a lot more attention to other factors such as profitability, defensiveness, and valuation when they are choosing which growth stock to buy.

Some so-called “growth” managers are more “quality”-orientated, emphasising things like return on invested capital and the consistency of growth, while others bill themselves as “growth” but make stock selection decisions that look more like “momentum” (adding to stocks that have been performing well while exiting their underperformers). Putting together a table that compares the returns of all these different types of “growth manager” will not necessarily tell who has added the most underlying value.

In my view, the best solution to this issue of distinguishing which aspects of a fund manager’s performance is due to market style factors and which aspect is due to their underlying relative performance is by undertaking a multi-factor regression which seeks to explain the fund manager’s performance in terms their exposures to market factors.

If the fund manager has consistently outperformed to a greater extent than is explained by these style factors, then you’re starting to get good evidence that they are really adding value in terms of the specific stocks they choose to invest in. Unfortunately, my observation has been that the majority of active fund managers seem to have detracted value once you back out those aspects of their performance that can be explained by market factors.

For our own fund (Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund), our own analysis indicates that we have added significant value beyond our factor tilts (we showed this in a graph in our September Fact Sheet). We are obviously biased, but investors may want to ask their advisors to provide them with factor analysis showing how different fund managers have performed after adjusting for factor biases.

Conclusions

Stocks of a feather flock together, and this flocking behaviour can be measured using style factors.

I believe that the studying the performance of style factors over the past 30 years provides valuable insight about how these factors are likely to perform over the next 30 years.

Factor returns also have a short-term tendency to trend, which means that the factors that worked last month are also likely to work next month, although this trending behaviour does not last for very long.

Style factors can also be a very useful tool for interpreting fund performance, and for differentiating the short-term drivers of fund performance from the underlying, arguably more persistent aspects of performance.

Nicholas Bagnall is chief investment officer of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited, and an investor in the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios (including the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund) that invest in global equity markets.