Australian Equities don’t deserve a special place in New Zealand investment portfolios

NBR Articles, published 10 June 2025

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall,

originally appeared in the NBR on 10 June 2025.

Many New Zealanders have a substantial allocation to Australian equities.

For example:

- The largest KiwiSaver fund has 12.4% of its funds invested in Australian equities, compared to 12.1% in New Zealand equities and 43.8% in non-Australasian equities;

- Many individuals have personal share portfolios that are heavily weighted to Australia; and

- Many local fund managers choose to manage “Australasian Equity Funds” rather than New Zealand equity funds. Some of these funds have significant allocations to Australian equities.

The home-bias vs neighbour-bias

It is well-known, New Zealanders have a significant home-bias in their investment portfolios. The New Zealand share market represents only about 0.06% of the global share market, but many New Zealanders hold somewhere between 15% and 35% of their equity investments in New Zealand companies.

Home-biases are common around the world, and New Zealanders’ allocations to their home country are actually quite low by global standards.

However, the more unusual aspect of how New Zealanders allocate our share portfolios is that we exhibit a strong “neighbour-bias”. The Australian share market represents about 1.75% of global share market capitalisation, yet many New Zealanders have between 10% and 30% of their share portfolios invested in Australian equities.

The home-bias can be rationalised

The home bias in favour of New Zealand equities can be rationalised in many ways, for example:

- New Zealanders investing in New Zealand companies get the benefit of imputation credits, which means that they pay less tax on investments in NZ Equities than they do for investments in foreign equities;

- New Zealand equities also avoid the FIF regime (the New Zealand tax regime which applies to non-Australasian equities and to Australian stapled securities), which also helps to reduce the tax liability on NZ equities relative to global equities;

- If you prefer to invest directly, many New Zealand brokers will take a clip of about 1% on the foreign exchange transaction needed to facilitate the purchase (and ultimately the sale) of any foreign investments. You can avoid this foreign exchange “clip” by investing in NZ equities rather than foreign equities. (Another way of reducing foreign exchange costs to invest in NZ-domiciled global equity funds, where the fund will convert the foreign exchange for you at a cost of less than 0.01%.);

- New Zealanders investing in New Zealand equities avoid the foreign exchange exposure of foreign equities and are buying a future stream of New Zealand dollar dividends that may be better matched to their future expenditure needs than investment income denominated in other currencies;

- New Zealanders directly investing in New Zealand consumer-facing companies may have better insight about the competitive advantages of the company than will typically be the case when they invest in similar businesses offshore;

- Patriotic motives will also mean that many people prefer to have a significant investment in New Zealand. Similarly, some people may like to hold shares in a New Zealand company because of a personal or emotional attachment to that company.

The neighbour-bias is harder to understand

While we can easily rationalise why New Zealanders hold significant allocations in New Zealand equities, the bias towards Australian equities is more of a puzzle and is more unusual in an international context. Is there some logical reason why New Zealanders should prefer Australian equities over other global equities?

Most of the reasons why New Zealanders can rationalise a home bias towards New Zealand equities do not apply to Australian equities. However, Australian-listed-and-domiciled companies are generally exempt from the FIF regime, which means that although NZ investors pay more tax on Australian equities than on New Zealand equities, they generally pay less tax on Australian equities than they do on non-Australasian equities.

However, it is not always obvious that avoiding the FIF regime is the motivating reason for larger allocations to Australian equities. For example, when I was looking at the Australian holdings of the country’s largest KiwiSaver fund, I noticed that six of the fund’s ten largest Australian-listed companies (excluding ASX-listed shares in NZ companies) were not eligible for an exemption from FIF taxes. In four cases, this was because the fund held stapled securities (which do not get the FIF tax exemption) and in two cases it was because the ASX-listed companies were legally domiciled in the United States.

Australian Equities are risky!

When measured in New Zealand dollar terms, Australian equities are very risky. Based on monthly data for the past 10 years, we can make the following observations about Australian equities:

- The NZ dollar returns from Australian equities have been more volatile than either New Zealand or Global Equities (with an annualised standard deviation of 15.0% vs 11.5% for NZ equities and 11.4% for global equities).

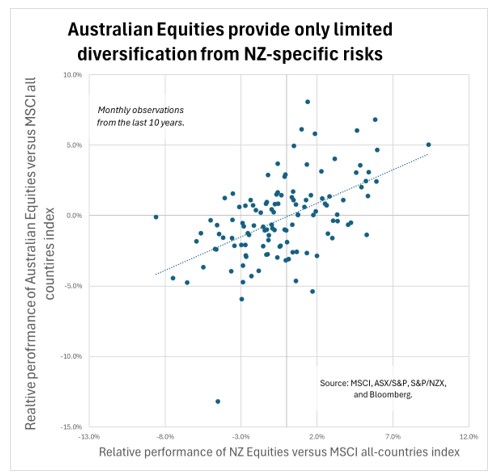

- Australian equities provide less diversification against New Zealand-specific risks, than global equities, as the Australian sharemarket tends to outperform and underperform the rest of the world at the same time that New Zealand does, as can be seen in the graph below:

- Australian equities are more sensitive to global equity markets than New Zealand equities. Over the past 10 years, New Zealand’s share market has had a remarkably low beta (sensitivity) to global equity markets of just 0.54, but Australia has had a much higher beta of 0.97.

- The tendency of the Australian dollar to rise and fall with global share markets has contributed to the riskiness of Australian equities. While one solution to this might be to overlay currency-hedging of investments in Australia, the Australian dollar is an expensive currency to hedge, as the currency forwards market prices in an implicit expectation that the New Zealand dollar will rise against the Australian dollar over time.

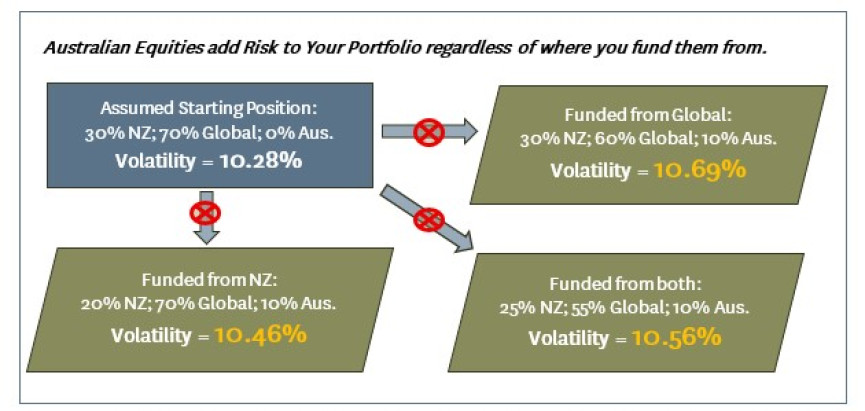

Accordingly, my analysis (based on the risk characteristics over the past 10 years) indicates that if your starting position is a portfolio that has a mix of New Zealand equities and global (non-Australasian) equities, any allocation to Australian equities will add to your overall risk profile, regardless of whether you fund the Australian allocation out of New Zealand equities or global equities.

The Australian Market is Expensive

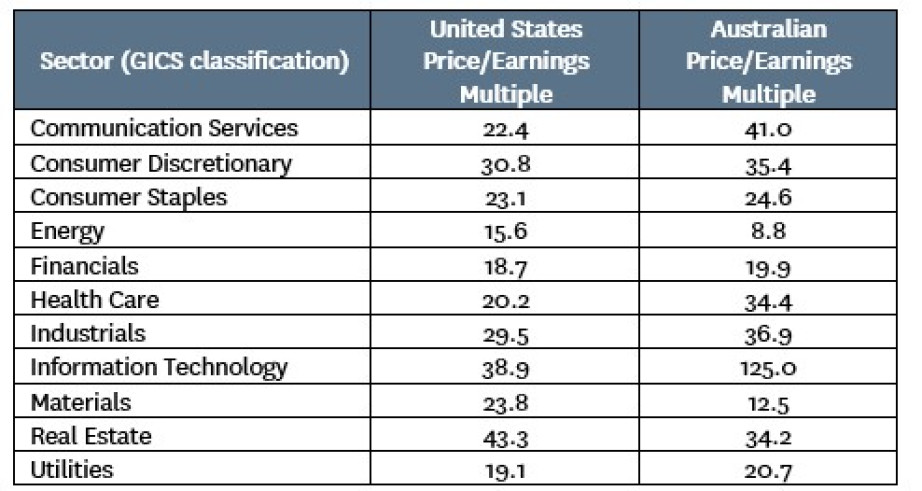

On a sector-by-sector basis, the Australian market is arguably the most expensive share market in the world. While the aggregate earnings multiple of the Australian share market only places it as the second-most expensive market in the world, behind the United States, the US market is dominated by stocks in growthy capital-efficient sectors that arguably justify higher multiples, whereas the Australian market is skewed to capital-intensive sectors like Financials and Materials.

Indeed, if we compare the P/E multiples of the Australian share market to the US share market on a sector-by-sector basis, we can see that Australian market is more expensive than the US market in 8 out of 11 sectors:

The only sectors where Australia seems to be cheaper than the United States are Energy, Materials, and Real Estate. Australia is arguably over-supplied with resource companies, which allows its Energy and Materials sectors to be reasonably priced. But the apparent relative cheapness of its Real Estate sector is illusory, as a difference in accounting treatment means that US Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) report earnings after the deduction of depreciation, whereas Australian REITs report their earnings prior to depreciation.

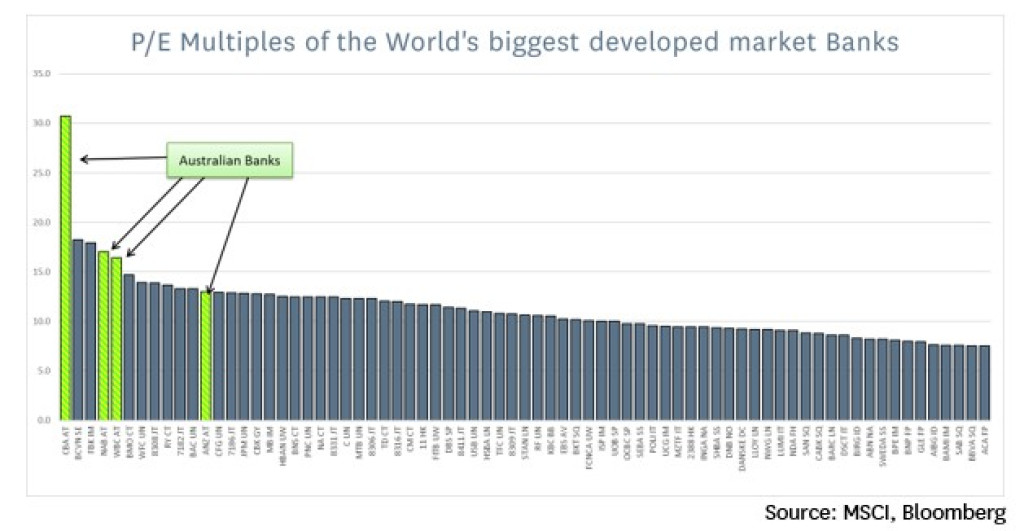

As another example of how expensive the Australian market really is, consider the following graph showing the price/earnings multiples of 73 of the 74 banks included in the MSCI World Banks index (I exclude one loss-making bank from the graph). Three Australian banks rank among the 5 most expensive in the world (out of the 74 largest banks), with CBA standing out as appearing to be priced in a completely different universe from all the other banks.

There is no obvious reason why Australian banks should deserve a premium rating. Australia has one of the highest ratios of household debt to income in the world, which implies a lower opportunity for future growth and a greater risk to existing lending than is the case in other countries.

Another indicator of how a weight of money seems to be inflating the value of Australian-listed shares is in the relative pricing of dual-listed shares. For example, Rio Tinto has a dual-company structure, whereby shares in Australian-listed Rio Tinto Ltd receive the same dividends and have the same voting rights as shares in UK-listed Rio Tinto plc. In theory, you might think that shares carrying identical rights might trade at a similar price in the two markets, but the reality is that the Australian shares trade at a 21% premium to the UK shares. The Australian shares are slightly more valuable for Australian shareholders, as they come with Australian franking credits attached to the dividends, but these credits are of no value to New Zealand shareholders.

BHP used to have a similar dual-company structure, with a similar discrepancy in the pricing of the two securities, such that the UK shares outperformed the Australian shares by +22% in 2021 when BHP unwound the dual-company structure in favour of operating as a single company (thereby eliminating the UK discount). Rio Tinto could choose to do the same thing.

Why is the Australian Market so Expensive?

In my view, the expensive pricing of the Australian equity market mainly reflects the weight of money from Australian compulsory superannuation, combined with a significant home bias by Australian superannuation schemes. Australia has had compulsory super for a lot longer than we’ve had KiwiSaver and (as its name suggests) it’s compulsory. Accordingly, the total size of the Australian Superannuation market has risen to a whopping A$4.13 trillion (NZ$4.46 trillion), 37 times as large as the pool of KiwiSaver money. The largest superannuation funds allocate an average of about 22% of their total assets to Australian listed equities and also have allocations to property and infrastructure that may be partly invested in Australian listed equities. Their Australian home-bias is at least partly justified by Australian franking credits (similar to New Zealand’s imputation credits).

These numbers imply that Australian Super schemes probably own about half of the Australian share market, whereas KiwiSaver funds probably own about a quarter of the New Zealand share market.

Ultimately, the high pricing of Australian equities is working to reduce the cost of capital for Australian corporates, which ultimately results in lower returns on equity, lower dividend yields on Australian stocks, and therefore an outlook for poorer returns in the future. While the trend over the last 3 decades has been for a lot more money to flow into Australian superannuation funds than is being taken out by retirees, the gap between contributions and withdrawals has been narrowing, which indicates that the inflating effect that this compulsory superannuation money has on the pricing of Australian equities may start to recede over time.

Why do New Zealanders allocate so much to Australian Equities?

“Why” questions can be answered in two different ways. Ideally, the answer to a why question is that you’re doing something to meet a current or future need. But often the real answer to a “why” question is no longer a current reason but instead is a remnant of history.

For example, the reason why whales have flippers and tails is to help them swim, but the reason why that they have hip bones (unattached to anything else) is just a remnant of history (they evolved from land mammals and never completely lost the genes that produce the hip bones).

In my view, New Zealander’s high allocations to Australian equities are, like the hip bones of whales, just a remnant of history, which does nothing at all to help NZ investors efficiently meet their current objectives.

Historically, it was very difficult for New Zealanders to invest directly offshore. Information (annual reports, analyst reports, financial newspapers, etc) came by post, and when this information came from Europe or America, it would be out of date by the time it got to New Zealand. Arranging custody and settlement in non-Australasian markets could also be difficult for NZ brokers. Most New Zealand broking firms could facilitate transactions in Australian equities, but could not easily help people who wanted to invest further afield. Hence, direct share portfolios that were built 30 or more years ago often contain only New Zealand and Australian stocks.

The funds management industry also developed in a way that led to an Australian bias. The current New Zealand funds management industry primarily consists of companies that started out as NZ Equity specialists and then gradually expanded into other asset classes. For firms that started out managing New Zealand equity portfolios, selectively adding Australian stocks into an existing New Zealand share portfolio was a logical “next step”, which has meant that we’ve ended up with a lot of “Australasian” equity portfolios. Many of these firms have been far more successful in the management of their Australasian equity portfolios than they have been with global equities, which may help explain why they continue to make significant allocations to Australasian equities.

Conclusion

Unless you spend a couple of months a year living in Australia, Australian equities probably do not deserve a special place in your investment portfolio. From a risk perspective, they are inferior to both NZ Equities and Global Equities. When it comes to long-term return, the expensive pricing of the Australian equity market increases the odds that it will underperform the rest of the world over the next 10 to 20 years.

Nicholas Bagnall is chief investment officer of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited, and an investor in the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios (including the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund) that invest in global equity markets. About 0.75% of the funds that Te Ahumairangi manages are invested in Australian equities. Nicholas Bagnall also holds direct investments in Australian equities totalling about 0.25% of his net financial worth.