Could the United States become “Uninvestible”?

NBR Articles, published 1 April 2025

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall,

originally appeared in the NBR on 1 April 2025.

When the BRIC share markets (Brazil, Russia, India, China) roared into life during the first decade of this millennium, many investors and fund managers deliberately stayed on the sidelines despite the fact that these share markets had initially been trading on very cheap valuations.

In many cases, their rationale for avoiding the BRICs was that the governments in these countries were too unpredictable and erratic and were not committed to the established conventions and treaties that put limits on how governments in other parts of the world would behave when dealing with businesses and investors.

Some fund managers were particularly wary about China, where the Chinese Communist Party was (and still is) in control. They felt that it was dangerous to invest in a country that was ruled by a clique that had no ideological leaning towards capitalism. Some fund managers and strategists argued that China had taken in foreign capital simply because it had helped China achieve its economic objectives at a particular point in time, but that the CCP would not hesitate to take back control if it believed that private capital was no longer helping it to achieve its goals. I recall several fund managers telling me that they regarded China as “uninvestible” and therefore held no Chinese equities.

At the root of their thinking was a view that it was dangerous to invest in a country’s businesses if you could not depend on country to follow a consistent and principled approach to dealing with businesses. In many ways, this viewpoint has been supported by economic history.

In his excellent economic history of the world, “A Farewell to Alms”, Gregory Clark showed that real incomes per capita did not sustainably increase for thousands of years (using data going back to ancient Babylon in 3500BC) until 1800AD. For all these millennia, the global economy seemed to be caught in a Malthusian trap whereby aggregate GDP grew very slowly over time, and any technological advance which allowed a country to increase its output was promptly followed by an increase in population which ensured that real income per capita stayed just as low as it had been before. For people in the bottom half of the economic heap, incomes were so low that they would often starve to death if there was a poor crop or if a recession or personal mishap left them unable to find work.

This only started to change with the industrial revolution, which began in England between 1780 and 1800, and then spread around the world. The modern phenomena of real incomes rising over time started with Britain and (shortly thereafter) its closest trading partners from about 1800, but only made it to China and parts of Africa by about 1970. Clark argues that one of the many reasons why the industrial revolution started in England (rather than in any of the more feudal countries that existed at the time) was that England had a constitutional monarchy and a well-defined system of laws and property rights which meant that merchants and industrialists could advance in economic and social status purely on the basis of their commercial endeavours, without having to win the favour of an aristocrat or worry that the local lord might seize assets or close their business down.

In short, capitalist economies tend to thrive when businesses can safely assume that governments will treat them fairly and consistently and that changes in regulations and taxes will be driven by broad policy objectives rather than erratic favouritism or score-settling.

What’s happening in the United States?

Recent developments in the United States seem to indicate that principle-based policies and treaties with other countries are on the way out. Instead, we are seeing rapid-fire changes to tariffs, and regulations. In many cases, these changes violate treaties with other countries, but the Trump administration seems to feel little compulsion to honour agreements made by past administrations (even agreements made by the first Trump administration, as indicated by Trump’s plan to impose new tariffs on Canada and Mexico).

There have also been actions that seem to be motivated by favouritism or score-settling, such as directions to award government contracts to Elon Musk’s StarLink, and orders directing the US government to not do business with large law firms that had previously represented clients taking legal action against Donald Trump. Companies that had previously been involved in disputes or court actions with Trump have been cowered into paying money to settle these disputes, rather than taking the risk that Trump will weaponise the government to take revenge on these firms.

What might Trump do next?

What might Trump do next? To date, his actions have not had a direct negative impact for many listed companies, but nothing seems to be off the table.

Trump’s economic interactions with other countries have largely consisted of imposing (or threatening to impose) tariffs on imports of goods into the US, and it is likely that other countries’ responses to these tariffs will initially be focused on reciprocal tariffs. However, since the US imports a much higher value of goods than it exports, there is a limit to the extent by which other countries such as the EU can reciprocate by placing tariffs on the import of goods from the United States.

It therefore seems inevitable that if the trade war escalates, many countries will find other ways of reciprocating against the United States, such as placing tariffs and levies on other sources of income that the United States derives from the rest of the world. In particular, US information technology companies derive significant income from the rest of the world but currently pay very little in the way of tariffs or taxes on these revenues. For example, Microsoft and Alphabet’s Google are both very profitable businesses, with operating margins of around 40%, and each achieve over a billion dollars of revenue from New Zealand, but between them they are only paying $21 million of New Zealand income tax. If the US imposes heavy tariffs on foreign countries, these foreign countries are likely to scrutinise the mechanisms by which US companies use transfer pricing and “reselling” of US services to minimise the local taxes they pay outside of the United States.

Other ways in which the rest of the world could threaten to hit back at the United States could include placing restrictions on the sale of strategically important items to the US. For example, Canada could cause brownouts by turning off the sale of gas and electricity to the US, while Japan or Europe could destroy America’s semi-conductor ambitions by banning the sale of semi-conductor manufacturing equipment to the United States.

There may also be some possibility that tensions between the US and other countries could lead to the cancellation of Double Tax Agreements between the United States and other nations. This would have serious implications for equity markets, as it could mean that residents of some countries may end up paying tax twice on dividends that they receive from US companies.

Of course, another risk to global equity markets is that Trump follows through with his talk of seizing Greenland. Such an action would likely lead to extreme hostility between the US and Europe, and a collapse of NATO. In such a scenario, it is easy to envisage widespread divestment of US investments by European investors.

If the current US administration continues to take the attitude that “anything is OK” when it comes to exerting leverage on other countries, there may be a risk that it considers seizing the foreign exchange reserves of other countries, a large portion of which are invested in US treasuries. This must be of particular concern to China, which the US clearly regards as an enemy. To reduce this potential risk, it would seem to make sense for countries with large foreign reserves to try to reduce their exposure to US assets. Japan has already said that it intends to increase the diversification of its international reserves, and I would not be surprised if other countries follow Japan’s lead.

One point that should be slightly reassuring to investors is that Trump still seems to be a fan of capitalism and property rights, so he will not intentionally want to implement policies that hurt corporate profitability, and would likely stop short of seizing privately-held assets in the United States. While he seems to have negative views about many liberal democracies around the world, and does not seem too concerned if a few companies get caught in the “cross fire” of his tariffs and export restrictions, it seems unlikely that he will do anything to deliberately hurt US companies, except for maybe a handful of US corporates that he has a particular grievance against (media companies in particular).

How is this affecting the share market?

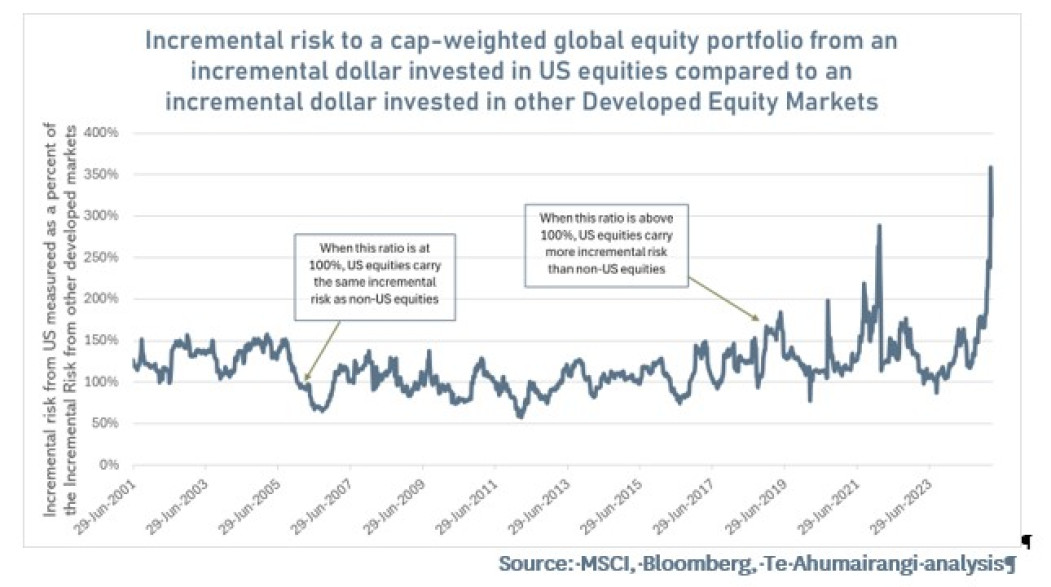

The policy uncertainty in the United States has contributed to making US-specific factors the dominant source of risk in any capitalisation-weighted global equity portfolio. This can be seen in the graph below, where I show how the incremental risk of investing an extra dollar in US equities compares to the incremental risk of investing that extra dollar in non-US developed market equities. (This graph looks at risk from the perspective of an NZ-based investor who already holds a global equity portfolio weighted according to the MSCI All Countries Index, and who measures risk in terms of the standard deviation of the weekly NZ dollar returns from their investment portfolio).

As can be seen from the graph, it has been historically normal to find that an incremental dollar invested in US equities is slightly riskier (for a New Zealand based investor) than an incremental dollar invested in non-US developed market equities. Up until the end of 2020, investing incremental funds in US equities was on an average of 12% riskier than investing those incremental funds in non-US developed market equities.

However, in recent months, investing in the United States has got a lot more risky, such that investing an extra dollar in the United States now adds 3 times as much risk to your portfolio as investing that incremental dollar in other developed country equity markets.

Historically, there has been an inverse relationship between the relative riskiness of the US equity market and the subsequent relative performance on the US equity market. Based on this historical relationship, we could expect US equities to underperform rest-of-developed-world equities by 5.7% over the next 12 months.

Indeed, the US share market has been underperforming equities from the rest of the world since the start of the year. Measured in NZ dollar terms, the US equity market has delivered a negative return of -7.09% so far this year, which compares very unfavourably with positive returns of +5.95% from the rest of the developed world and +2.51% from emerging market equities. This more than offsets the outperformance of US equities that occurred at the end of 2024 after the US election.

Do the risks make the United States Equity Market uninvestible?

To my mind, risk never makes limited liability assets completely uninvestible. Instead, heightened risk should logically reduce the price you are prepared to pay for an investment, and reduce the proportion of your portfolio that you are prepared to invest in it.

For example, at the start of the article, I talked about how many investors had avoided the BRIC equity markets because they perceived that these markets were uninvestible. But if you’d invested in the 4 BRIC markets in equal proportion in 2001 (when the “BRIC” term was first coined by a Goldman Sachs strategist), you would have ended up with slightly higher returns than you would have seen from developed market equities. While the money you’d invested in Russia would have been completely wiped out after the invasion of Ukraine, strong returns from the Indian share market (+11% per annum in NZ dollar terms since 2001) have been sufficient to offset the Russian wipeout. But the returns from the BRICs have been very uneven over time, with all of the BRIC markets significantly outperforming developed market equities over the 7 years between 2001 and 2008, but significantly underperforming in the 16¼ years since the end of 2008.

So even though the BRIC markets had “uninvestible” characteristics (similar to what we might be seeing emerging in the US now) they delivered (on average) good returns if you bought them while they were cheap (in 2001) and diversified your investments such that Russia did not represent too large a share of your portfolio.

However, saying that “uninvestible” markets can be okay if you are buying them cheaply and don’t put too many of your eggs in that basket is hardly a ringing endorsement of most investors’ investment in US equities. As I have pointed out before (in my column of 26 November), US equities are not cheap, and in fact are significantly more expensive than equities in other parts of the world. And investors in the US equity market are typically not well diversified into other countries. For example, many “international equity” investment funds have allocations of more than two thirds of their assets into US equities.

I don’t have any strong insight about whether the Trump administration’s erratic approach to dealing with other countries may escalate to the point that it directly affects investors’ holdings of US equities, or whether the extreme tariff / 51st state / Greenland invasion proclamations are just negotiating positions that will never be acted upon. However, it does seem to me that the specific risk associated with investing in the United States are now too high to justify allocations of 70% or more of investors’ global equity allocations into a market that is in trading on much higher valuation multiples than other countries around the world.

Nicholas Bagnall is chief investment officer of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited, and an investor in the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios (including the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund) that invest in global equity markets. These portfolios hold shares in the following companies mentioned in this column: Microsoft and Alphabet (parent of Google). The portfolios managed by Te Ahumairangi hold a weight of about 44% in US equities, markedly lower than the 71.5% weighting that United States has in the MSCI World index.