Does it really make sense to have over 60% of your offshore investments in the United States?

NBR Articles, published 14 February 2023

This article, by Te Ahumairangi Chief Investment Officer Nicholas Bagnall,

originally appeared in the NBR on 14 February 2023.

Investors in mainstream New Zealand based global funds, multi asset class funds, or KiwiSaver funds invariably have a large exposure to the United States. Typically, more than half (and sometimes over 70%) of the non-Australasian component of these funds is invested in the United States.

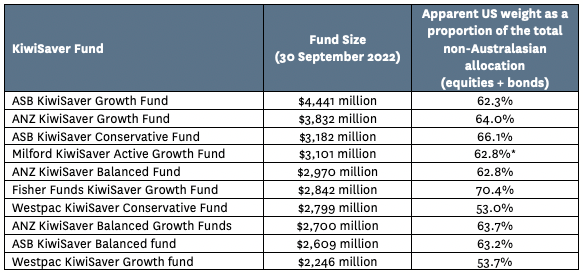

For example, consider the following table, showing the 10 largest KiwiSaver funds, with my calculation of what proportion of the non-Australasian component of these funds is invested in the United States.

For the rightmost column of this table I have used the funds’ reported security identifiers to calculate the exposure to each country. Due to the security identifiers used, I was not able to do this for bond holdings in the Milford fund, and it appears that Milford’s US weighting would be lower if bonds were included.

Why do NZ fund managers have so much invested in the United States?

A key factor driving these high allocations to the United States is the similarly high weighting of the United States in indices designed represent the global share market, such as the MSCI All Countries World Index (“MSCI ACWI”), where the US market has a 60.4% weighting. Many fund managers try to keep their actual equity allocations close to the benchmark, which in most cases is the MSCI ACWI.

In theory, the country weightings of the MSCI ACWI are intended to reflect the relative size of the investible market in each country, although the US is slightly over-represented relative to this metric. By MSCI’s own calculations, the United States only represents 59.4% of the global investible market. Other countries, such as New Zealand and Japan, are under-represented in the index due to a large proportion of the capitalisation of their sharemarkets being represented by companies that are deemed too small to be included in the MSCI index.

There is more variety in the benchmarks that KiwiSaver managers have chosen for their global fixed interest allocations, but the United States market generally has a lower weighting in these indices, typically around 40%. The observation that global equity benchmarks are about 60% weighted to the United States and global fixed interest benchmarks are about 40% weighted to the United States yet many fund managers have over 60% of their global funds invested in the United States would suggest than many of them are either intentionally or unintentionally tilting towards a higher US weighting than is included in their benchmarks.

The theory of capitalisation-weighted benchmarks

If we momentarily disregard the modest tilt that many fund managers seem to have towards the States in comparison to their benchmarks, we have a first-order explanation of why these funds have a high allocation towards the United States (they’re following capitalisation-based benchmarks) but haven’t really addressed the second order question of whether such an approach makes sense if they’re trying to get the best combination of risk and return for people who are relying on these KiwiSaver funds for their retirement.

Conventional finance theory suggests that capitalisation-based indices should provide a close-to-optimal combination of risk and return for most investors. The assumptions under-pinning this theory are that most other investors are busily researching the potential risks and likely returns of every publicly tradable investment security, and the relative pricing of different securities should therefore fully reflect everything that is knowable about those securities. The theory also presumes that “risk” looks more or less the same to all investors regardless of factors such as their time horizons, their investment objectives, or the different currencies that they measure their returns in.

Following this “efficient markets” theory, we would conclude that if the collective actions of a lot of thoughtful investors have valued the US sharemarket so highly that it represents 60% of global equity market capitalisation, then surely US equities either offer sufficiently high returns or sufficiently low risk that they justify a 60% weight in global equity portfolios.

A key problem with this theory is that when you look at how investors around the world are actually allocating funds between different equity markets, you see scant evidence of the research and deep thought that the theory presumes. In each country, investment funds seem to allocate between domestic and international allocations by choosing an allocation that closely reflects the average allocation of their domestic peers, as the sponsors of the funds are often very concerned with the risk of being embarrassed about lagging their peers in any given year. American funds typically have a stronger bias towards domestic equities than most other countries, which has the effect of boosting demand for US equities relative to non-US equities.

Most funds then benchmark their international equity allocation against a capitalisation-weighted benchmark such as the MSCI ACWI (or the version of the MSCI ACWI that omits the local sharemarket). Increasingly, global funds have been allocated to passive strategies (which will exactly replicate the benchmark). But even when global funds are given to active fund managers, many of the fund managers are very benchmark-aware, trying to keep the proportion of their funds that are invested in each country to within 2 or 3% of the benchmark.

When I was first talking with global equity managers in the 1990s, the majority of global equity managers took a “top-down” approach to country allocation, starting off portfolio construction by assessing the relative attractiveness of each equity market before moving onto picking stocks in each market. This approach has since fallen out of fashion, and the vast majority of active global equity managers now pick stocks using a “bottom-up” approach. This means that while there is a lot of money and effort still being applied to identifying over- or under- valued individual companies, there is now relatively little money and effort being devoted to identifying over-or under-valued national share markets.

The New Zealand Superannuation Fund is a bit of an exception to this general rule, in that it holds most of its global equity allocation in passive portfolios (effectively choosing not to try to add value through analysis of individual companies) yet undertakes a “strategic tilting” program which (amongst other things) aims to exploit the relative over- or under- valuation of different share markets. The success that the NZ Superannuation Fund has had with its strategic tilting program is perhaps evidence of the vacuum of market attention with respect to the relative valuation of different share markets, which should be a warning sign for those who presume that the United States’ high weighting in global share market indices must be an efficient synthesis of the collective analysis of millions of diligent investors.

Does the high US weighting make sense from the perspective of investor risk?

In theory, the best way of determining how to allocate your global equity exposure between the United States and other markets would be to estimate the long term returns and risk characteristics of each market, and then optimise to find the weightings that would produce the best overall combination of risk and return. In practice, this requires extensive analysis and judgments, which I could not properly cover in the space of one column.

However, a good starting point for estimating the risk characteristics of each equity market is to look at history. The US share market looks more volatile than the rest of the world on the basis of daily returns but has a very similar volatility to the rest of the world (in aggregate) when you look at monthly returns. Based on the historical pattern of monthly returns, an asset allocation optimiser would tell you that an allocation of about 50% to the United States is roughly appropriate.

Given the estimation errors inherent in portfolio optimisation based on historical data, it is not clear from the historical pattern of returns that an allocation of 60%+ to the United States is necessarily inconsistent with finding an allocation between equity markets that minimises risk.

Of course, historical observations cannot tell you all that you need to know about future risk. In particular, investors should be aware that there will be risks specific to the United States that might not be apparent if you just look at a few years of historical data. For this reason, I would be cautious about accepting the conclusions of any optimisation analysis that suggests that a minimum risk position could be to put more than 50% of your eggs in the one basket.

Does a high US weighting make sense from the perspective of future returns?

If a high US weighting is not justified on risk grounds, perhaps the prospect of stronger future returns justifies a high allocation to US equities?

Market pricing does not suggest that it will be easy for the US market to deliver future returns that are comparable to other markets, as the US market is trading on a trailing price/earnings ratio of about 20 times earnings (an earnings yield of just 5.0%) where the European and Japanese equity markets are priced on trailing price/earnings ratios of under 15 times (an earnings yield of 6.7%). Companies in Europe and Japan can effectively afford to distribute an extra 1% per annum of cash to shareholders while retaining the same share of profits as their US peers to fund future growth.

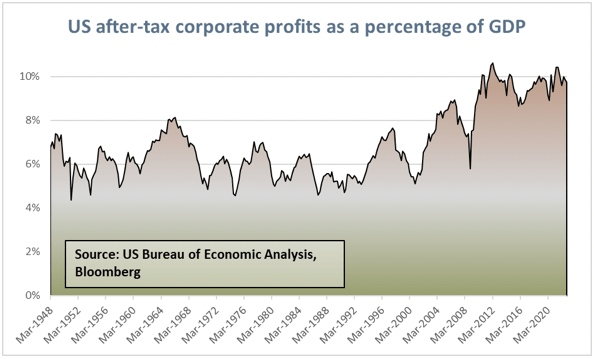

Further, US profits are currently at an elevated level by historical standards (see graph below) which indicates some risk that current levels of profitability may be unsustainable. In other countries, the current level of corporate profitability seems to be more in line with the historical range.

In particular, the earnings of many US listed companies seem to have been artificially boosted by all the economic stimulus that took place in response to the covid pandemic. For example, US retail sales in the last 6 months of 2022 were more than 31% higher than they had been in the last 6 months of 2019. As monetary policy becomes less accommodating and economic activity deflates to a more normal level, it is likely that many US businesses will struggle to maintain profitability. While other countries have also engaged in economic stimulus, it appears to have had less impact on demand, and there is therefore less risk from the unwind.

Disregarding these concerns, many fund managers and broker analysts with a predilection for technology stocks seem to find more stocks that they believe will deliver them attractive returns in the United States than in the rest of the world. Why is this?

One common mistake that I observe (with broker analysts at least) is that they treat US dollar returns for US stocks as comparable to (say) euro returns for European stocks. So they might (for example) prefer a US stock that they expect to deliver 9% returns measured in US dollars to a European stock that they expect to deliver 8.5% returns in euro or a Japanese stock that they expect to deliver 8% returns in Japanese yen. The problem with this blindness to currency is that the market doesn’t value future US dollars as highly as it values future cashflows in the euro or the yen, and this should be readily apparent to NZ investors if they lock in currency hedging for equities held in different parts of the world. When hedged to NZ dollars over a period of 5 years, an 8.0% return in Japanese yen becomes a return of 11.3% per annum in NZ dollars, and an 8.5% return in euro becomes 10.1% in NZ dollars, but a 9.0% return in US dollars would be just 9.5% when hedged to NZ dollars.

Another common mistake seems to be to ignore stock-based compensation (together with the associated dilution of existing shareholders). Even NZ-based fund managers seem to love to tout their favourite US holdings by quoting price/earnings ratios using “adjusted earnings” numbers that deliberately exclude the costs to shareholders of paying employees with scrip.

From a top-down perspective, if I assume that US corporates can in aggregate grow earnings at 4% per annum whilst distributing 60% of profits to shareholders, I see a long term return in US dollar terms of about 7% per annum (which improves to about 7.5% per annum when hedged to NZD). From a bottom-up perspective, we also typically see local currency returns of between 6% and 9% per annum when we look at individual US companies. In my experience, higher future returns seem far easier to identify for companies based and listed outside of the United States than they are within the US. From the current starting point, I therefore struggle to believe that the US share market has a good probability of delivering long term returns that justify it representing more than 60% of a global equity portfolio.

Nicholas Bagnall is Chief Investment Officer of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not, nor should be construed as, investment advice for any person. The writer is a director and shareholder of Te Ahumairangi Investment Management Limited, and an investor in the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund. Te Ahumairangi manages client portfolios (including the Te Ahumairangi Global Equity Fund) that invest in global equity markets. These portfolios currently have allocations to US equities of about 45%.